Researchers publishing in Nature Microbiology have determined that the viruses populating the intestines of centenarians are slightly different from those of the merely old.

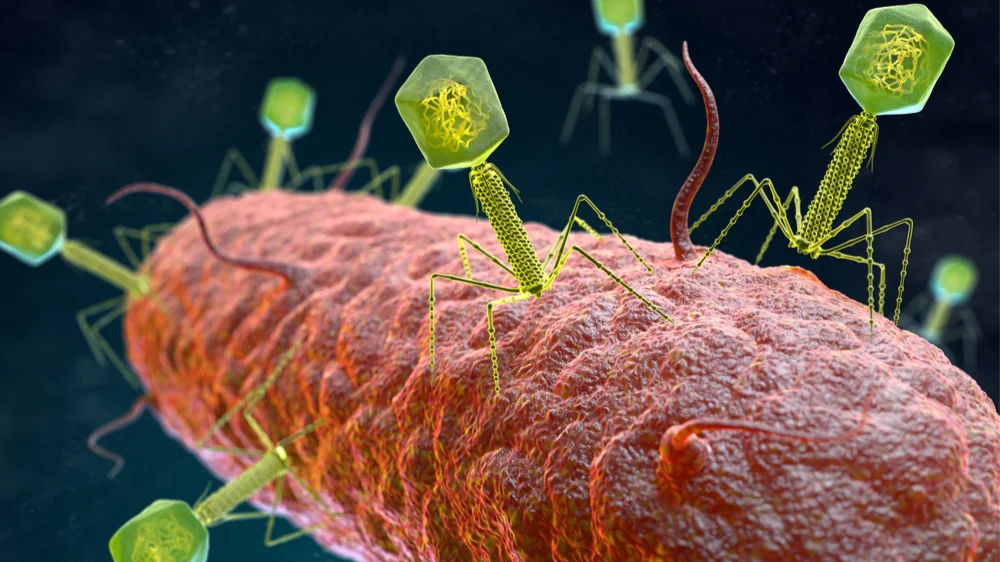

Viruses for bacteria, not people

We have written previously about a study showing that centenarians have youthful bacterial gut compositions (enterotypes) similar to those of younger people. This study looks more closely at that phenomenon, focusing on the viruses (bacteriophages) that infect the bacteria within the human gut.

While this is a niche subfield, there is a Gut Virome Database, and a previous analysis of this database has found that the populations of viruses in the gut change with aging [1]. The gut virome is likely to have significant effects on human health [2], and previous work has found that introducing certain viruses can improve cognition in multiple organisms [3]

Bacteriophages have two main methods of transmission. In lysogenesis, the virus integrates into the bacterium it infects, encouraging its division in order to propagate the virus as well. In lysis, however, the virus simply reproduces in a way that kills the bacterium, sending out infectious viral particles in the process [4]. Lysogenesis changes bacterial metabolism, and bacteria undergoing lysis are also affected before they die [5].

Very young children have chaotic microbiomes, but this stabilizes towards more lysogenesis and less lysis, which continues into adulthood [6]. Like with many other bodily functions, aging appears to disrupt this equilibrium as well. Previous work has found that inflammation increases the amount of lysis over lysogenesis [7], and age-related inflammation (inflammaging) is a known problem [8]. This paper looks deeper at this issue, attempting to determine a biological relationship.

An in-depth look at thousands of viruses

An operational taxonomic unit (OTU) is a term that refers to a group of closely related organisms that are fundamentally the same for the purposes of research. Using modern computers to analyze previously collected data in multiple ways, the researchers found 4,422 viral OTUs in the human-derived data it examined, 1,746 of which had never been described before. 12% of these viral OTUs were only found to be present in centenarians. This study found that older people have more viral diversity than younger people in general, which contradicts previous research [1].

Unfortunately, the researchers’ analysis showed, to an extreme degree of statistical significance, that centenarians were not protected against the age-related shift towards lysis. The researchers surmised that inflammaging was driving otherwise lysogenic viruses towards this state. The researchers also noticed a shift in viral species, and that shift was found to be maintained in centenarians.

There was, however, a similarity between centenarians and younger people that was not shared by people in between. The bacteria within centenarians continued to process various sulfur metabolites more similarly to young people, and the researchers believe that this is due to the lysogenetic viruses’ genetic effects.

A very simple chemical might be the key

While this paper is rich with in-depth genetic analysis, the researchers believe that a very simple chemical, hydrogen sulfide, might be a critical part of the health of very old people. This is produced at the end of sulfur metabolism, and high concentrations can kill oxygen-breathing gut pathogens before they take hold [9]. In this way, the viruses encouraging this metabolism may be protecting the gut, and the rest of the person, from harmful infections.

That is still only a hypothesis with the evidence at hand, and the researchers also note that their tools may be slightly flawed, as the various analyses they used did not entirely agree with one another. Even with that, this research points towards a potential addition to gut microbiome-related therapies and reminds everyone that the bacteria themselves are not the only organisms in the gut.

Literature

[1] Gregory, A. C., Zablocki, O., Zayed, A. A., Howell, A., Bolduc, B., & Sullivan, M. B. (2020). The gut virome database reveals age-dependent patterns of virome diversity in the human gut. Cell host & microbe, 28(5), 724-740.

[2] Adiliaghdam, F., & Jeffrey, K. L. (2020). Illuminating the human virome in health and disease. Genome Medicine, 12(1), 66.

[3] Mayneris-Perxachs, J., Castells-Nobau, A., Arnoriaga-Rodríguez, M., Garre-Olmo, J., Puig, J., Ramos, R., … & Fernández-Real, J. M. (2022). Caudovirales bacteriophages are associated with improved executive function and memory in flies, mice, and humans. Cell host & microbe, 30(3), 340-356.

[4] Sutton, T. D., & Hill, C. (2019). Gut bacteriophage: current understanding and challenges. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10, 784.

[5] Howard-Varona, C., Lindback, M. M., Bastien, G. E., Solonenko, N., Zayed, A. A., Jang, H., … & Duhaime, M. B. (2020). Phage-specific metabolic reprogramming of virocells. The ISME journal, 14(4), 881-895.

[6] Shamash, M., & Maurice, C. F. (2022). Phages in the infant gut: a framework for virome development during early life. The ISME Journal, 16(2), 323-330.

[7] Gogokhia, L., Buhrke, K., Bell, R., Hoffman, B., Brown, D. G., Hanke-Gogokhia, C., … & Round, J. L. (2019). Expansion of bacteriophages is linked to aggravated intestinal inflammation and colitis. Cell host & microbe, 25(2), 285-299.

[8] Franceschi, C., Garagnani, P., Parini, P., Giuliani, C., & Santoro, A. (2018). Inflammaging: a new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 14(10), 576-590.

[9] Buret, A. G., Allain, T., Motta, J. P., & Wallace, J. L. (2022). Effects of hydrogen sulfide on the microbiome: From toxicity to therapy. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 36(4-6), 211-219.