According to a new study, the age-related increase in intestinal permeability that drives inflammation can be alleviated by inhibiting the enzyme arginase, a regulator of nitric oxide production [1].

Gut feeling

While age-related sterile inflammation (inflammaging) is considered one of the hallmarks of aging and a major cause of age-related diseases [2], scientists still don’t fully understand what causes it. Inflammation is a part of the immune response, and “sterile” means that there is no obvious reason for the immune system to react that way.

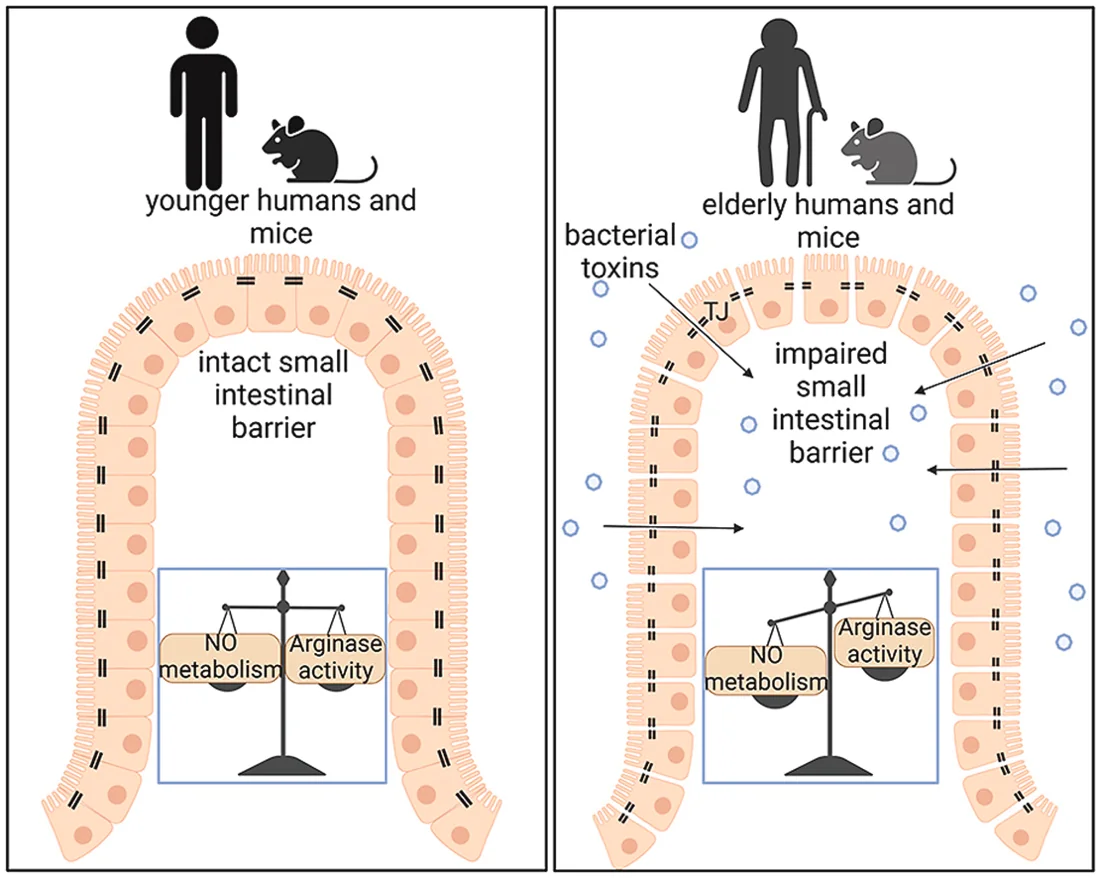

Recently, studies began pointing to the age-related increase in intestinal permeability as a possible culprit [3]. The gut is a front line that is constantly attacked by pathogens from food, air, and the vast population of intestinal bacteria. Intestinal epithelial cells must be able to let nutrients in while keeping those pathogens out. Like many other bodily functions, this one declines with age. The gut becomes “leaky”, and pathogens enter circulation and cause an immune response, or so the theory goes.

More permeability with age

In this new study, the researchers investigated some aspects of this theory in humans and mice. First, they ran blood tests on 16 young healthy and 16 old healthy participants. Having healthy participants allowed the researchers to determine whether intestinal dysfunction appears prior to any known diseases of aging. None of the subjects suffered from obesity, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver, chronic inflammatory diseases, or malignancies, and none of them were taking medications to control any of those.

Indeed, despite older subjects being healthy, several markers of intestinal permeability in their blood were significantly elevated compared to young controls, including bacterial endotoxins and the CD-14 protein, which enhances the body’s reaction to those toxins.

The same picture was seen in mice. In 24-month-old animals, bacterial endotoxins were more than twice as abundant than in younger controls. While intestinal morphology did not significantly differ between the two groups, both protein and mRNA levels of the tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 were significantly lower in the proximal small intestine of old mice. Tight junctions are connections between cells that hold them together, not unlike nails or rivets. Markers of cellular senescence were higher, and stem cell-related markers, such as telomerase, were lower in older animals. However, no such age-related differences were observed in the distal small intestine and colon.

No, it’s NO

Emerging research has attributed intestinal permeability to age-related changes in microbiotal composition, which indeed differed significantly between young and old mice. However, transplantation of microbiota from young to old mice failed to alleviate intestinal permeability in the latter. This stands in contrast with some recent studies in which various benefits of microbiotal transplantation were reported.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a simple but important molecule. Its healthy levels are associated with cardiovascular health, and it plays an important role in maintaining intestinal integrity [4]. With age, intestinal NO metabolism gets disrupted, while levels of arginase, a critical regulator of NO synthesis, go up, which is also what happened to the mice in this study.

Hence, downregulating arginase is a possible way to alleviate age-related intestinal damage. One previous study found that genetic deletion of arginase attenuates the onset of senescence and extends lifespan in mice [5]. This time, researchers used an arginase inhibitor rather than genetic engineering.

Arginase inhibition improves “leaky gut”

Treating old mice with the arginase inhibitor norNOHA for six weeks improved intestinal barrier function, lowered bacterial endotoxin levels, and decreased senescence markers in the liver while simultaneously increasing NO production.

Interestingly, despite those improvements, intestinal microbiotal composition was similar between old mice that had been treated with an arginase inhibitor and those that had not. The researchers hypothesize that “maintaining intestinal barrier function in aging may not depend solely on intestinal microbiota”, and that NO homeostasis in small intestinal tissue, regulated by arginase, is probably an important factor as well.

Here, we report that even in healthy older men low grade bacterial endotoxemia is prevalent. In addition, employing multiple mouse models, we also show that while intestinal microbiota composition changes significantly during aging, fecal microbiota transplantation to old mice does not protect against aging-associated intestinal barrier dysfunction in small intestine. Rather, intestinal NO homeostasis and arginine metabolism mediated through arginase and NO synthesis is altered in small intestine of aging mice. Intestinal arginine and NO metabolisms could be a target in the prevention of aging-associated intestinal barrier dysfunction and subsequently decline and ‘inflammaging’.

Conclusion

This study supports the idea that with age, the intestinal barrier loses integrity even in healthy people, which is likely to be a driver of inflammaging. Another important finding is that age-related changes in microbiota composition may not be the main cause of age-related intestinal dysfunction, and, consequently, microbiotal transplantation may not be the optimal solution. Slowing the age-related decrease in intestinal NO production via arginase inhibition, however, is an intriguing, novel strategy that deserves further research.

Literature

[1] Brandt, A., Baumann, A., Hernandez-Arriaga, A., Jung, F., Nier, A., Staltner, R., … & Bergheim, I. (2022). Impairments of intestinal arginine and NO metabolisms trigger aging-associated intestinal barrier dysfunction and inflammaging´. Redox Biology, 102528.

[2] Ferrucci, L., & Fabbri, E. (2018). Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 15(9), 505-522.

[3] Kavanagh, K., Hsu, F. C., Davis, A. T., Kritchevsky, S. B., Rejeski, W. J., & Kim, S. (2019). Biomarkers of leaky gut are related to inflammation and reduced physical function in older adults with cardiometabolic disease and mobility limitations. Geroscience, 41(6), 923-933.

[4] Mu, K., Yu, S., & Kitts, D. D. (2019). The role of nitric oxide in regulating intestinal redox status and intestinal epithelial cell functionality. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(7), 1755.

[5] Xiong, Y., Yepuri, G., Montani, J. P., Ming, X. F., & Yang, Z. (2017). Arginase-II deficiency extends lifespan in mice. Frontiers in physiology, 8, 682.