A paper published in Environmental Science and Technology has described some of the effects of nanoplastics on human liver and lung cells [1].

Microplastics and nanoplastics

Plastics in the environment are gradually broken down by sunlight, grinding processes, and biological activities into smaller and smaller pieces [2]. These are the infamous microplastics, but when they are ground down smaller than than a micrometer, they become nanoplastics [3]. At less than 100 nanometers, these particles are small enough to cross cellular membranes and be taken up by cells, rendering them potentially dangerous to those cells and to the organisms they constitute [4].

The liver, as a filtration and processing organ, is specifically known for being strongly exposed to plastics. Lung tissue is also known for being exposed to plastics in the air [5]. Therefore, the researchers focused on the cells of these two organs, analyzing the effects of nanoplastics at various concentrations.

A focus on polystyrene

This research used standardized 80-nanometer particles of polystyrene at various concentrations ranging from 0.006 grams per liter to .25 grams per liter. Normal liver cells and epithelial lung cells were grown on standard growth media for this experiment.

Interestingly, exposure to lower levels of nanoplastics, such as 0.0312 grams per liter, was found to slightly increase viability in liver cells; the researchers hypothesize that this was due to the liver tissue activating in order to fight what they perceived as a threat. At higher concentrations, however, the cells became less viable, being reduced to approximately 60% viability at the highest concentration tested. Interestingly, this effect was much less prominent in lung cells, which only lost roughly 20% of their viability at the highest concentration.

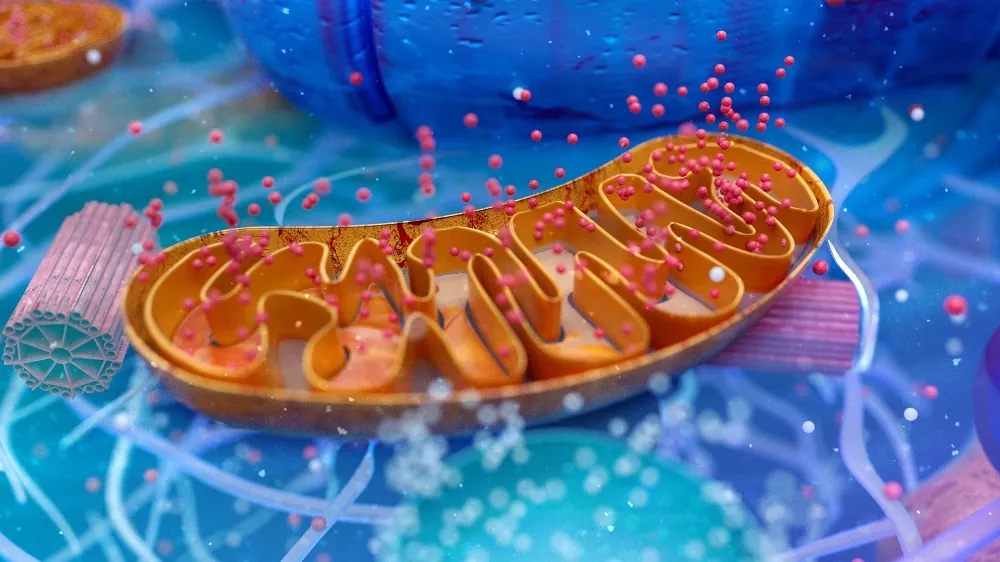

Mitochondrial effects

After learning that these levels were not immediately fatal to cells, the researchers then turned their attention to the mitochondria. Even relatively lower levels of nanoplastics were found to increase the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mROS).

The mitochondrial membrane was also studied. In liver cells, the mitochondrial membrane was somewhat damaged even at low concentrations, intensifying at the highest concentration. In lung cells, the dose-response relationship was less linear; low concentrations did little to the cells, but damage was seen at the highest concentration.

This was also true of respiration. ATP was impaired in liver cells at low concentrations, but lung cells reacted by increasing ATP instead; only at higher concentrations were the more toxic effects seen in those cells. Interestingly, liver mitochondria had less proton leak with increasing nanoplastic exposure, while lung mitochondria had higher. As expected, gene expression of fundamental metabolic activities was affected by nanoplastic exposure in both kinds of cells: liver cells showed more effects on mitochondrial electron transport, while lung cells showed more effects in urea production.

In total, the combinations of potentially positive adaptive responses in some areas, and direct harm in others, shows that nanoplastics at sufficient concentrations have significant effects on mitochondrial respiration and metabolism.

Abstract

Plastic debris in the global biosphere is an increasing concern, and nanoplastic (NPs) toxicity in humans is far from being understood. Studies have indicated that NPs can affect mitochondria, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The liver and lungs have important metabolic functions and are vulnerable to NP exposure. In this study, we investigated the effects of 80 nm NPs on mitochondrial functions and metabolic pathways in normal human hepatic (L02) cells and lung (BEAS-2B) cells. NP exposure did not induce mass cell death; however, transmission electron microscopy analysis showed that the NPs could enter the cells and cause mitochondrial damage, as evidenced by overproduction of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, alterations in the mitochondrial membrane potential, and suppression of mitochondrial respiration. These alterations were observed at NP concentrations as low as 0.0125 mg/mL, which might be comparable to the environmental levels. Nontarget metabolomics confirmed that the most significantly impacted processes were mitochondrial-related. The metabolic function of L02 cells was more vulnerable to NP exposure than that of BEAS-2B cells, especially at low NP concentrations. This study identifies NP-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic toxicity pathways in target human cells, providing insight into the possibility of adverse outcomes in human health.

Conclusion

One of the largest limitations of this study was that it focused on one specific size and type of nanoplastic particle at a consistent concentration. Other particulate polymers of slightly different sizes might have considerably different effects on mitochondria and other organelles.

However, this research does make it clear how and why polystyrene nanoplastics may be a danger to human beings, increasing oxidative stress and potentially leading to the acceleration of at least one aspect of aging in liver and lung tissue. Higher doses were shown to have a much more significant effect, especially in lung tissue signifying that minimizing exposure to these substances is likely to be a good idea, both on the personal and the policy levels.

Literature

[1] Lin, S., Zhang, H., Wang, C., Su, X. L., Song, Y., Wu, P., … & Zheng, C. (2022). Metabolomics Reveal Nanoplastic-Induced Mitochondrial Damage in Human Liver and Lung Cells. Environmental science & technology.

[2] Russell, A. E. (2004). Lost at sea: Where is all the plastic. Science, 304(5672), 838.

[3] Lai, H., Liu, X., & Qu, M. (2022). Nanoplastics and Human Health: Hazard Identification and Biointerface. Nanomaterials, 12(8), 1298.

[4] Vethaak, A. D., & Legler, J. (2021). Microplastics and human health. Science, 371(6530), 672-674.

[5] Zhang, Q., Xu, E. G., Li, J., Chen, Q., Ma, L., Zeng, E. Y., & Shi, H. (2020). A review of microplastics in table salt, drinking water, and air: direct human exposure. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(7), 3740-3751.