Tiny bubbles that cells use to communicate with each other prolonged lifespan and reversed numerous aging phenotypes when taken from young mice and injected into old ones, even though the treatment started late in life [1].

The tiny messengers

For millennia, humans credited young blood with rejuvenating qualities. This belief caused legendary and historic rulers to commit atrocities to get enough of this “elixir of youth”. While these ideas were delusional and barbaric, science has confirmed that there is some truth to them.

Research into heterochronic parabiosis, which involves connecting the vasculatures of a young and an old animal, has shown that it rejuvenates the old member of the pair and makes the young one age faster [2], but the mechanisms are still being elucidated. Recently, extracellular vesicles (EVs) carried by blood have been pinpointed as being responsible for many of these effects.

EVs are tiny bubbles made of a lipid bilayer, the same stuff cellular membranes are made of. Emitted by cells, they carry various molecular cargoes, such as proteins and microRNAs (miRNAs), and facilitate intercellular communication. EVs harvested from young blood have been shown to benefit old organisms [3], but since there are many molecules involved, the investigation into how exactly they do it is still very much ongoing.

Small size, big effect

EVs can be of various sizes, which might affect their qualities. In this new study published in Nature Aging by scientists from Nanjing University in China, the researchers focused on small EVs (sEVs) of less than 200 nanometers in diameter. They repeatedly injected old male mice with sEVs obtained from young mice or humans to explore their rejuvenation potential.

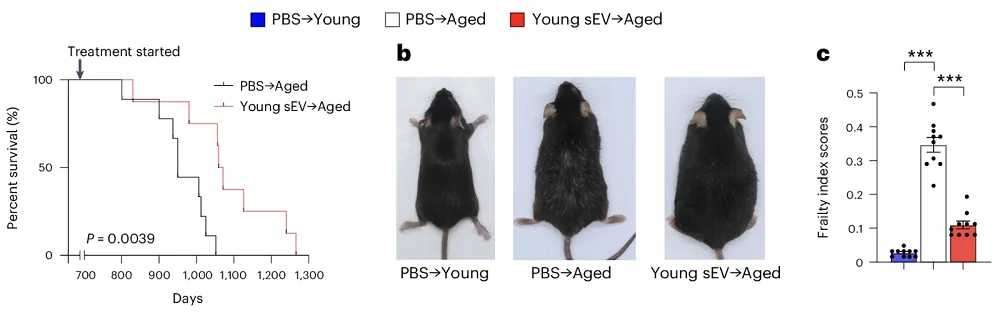

The old mice were injected with the sEV cocktail once a week starting from 20 months of age until death. Young and old controls were instead injected with the same dose of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

This led to an approximately 1/8th increase in median lifespan (34.4 vs 30.6 months), which is very significant given that the treatment only started when the mice were already quite old. It also improved various healthspan measures, such as frailty and hair retention.

The researchers analyzed various other aspects of age-related decline. For instance, just like humans, old male mice exhibit signs of reproductive aging, with lower levels of testosterone, low sperm count, and reduced sperm motility. However, the sEV treatment brought sperm concentration and motility, as well as litter size, back to levels comparable to those of young mice.

The good news didn’t end there. The treatment significantly improved the old mice’s fitness, as measured by heat production, oxygen consumption, and locomotor activity. It also increased cardiac performance, slowed bone loss, and partially rescued age-related loss of cortical and hippocampal volume.

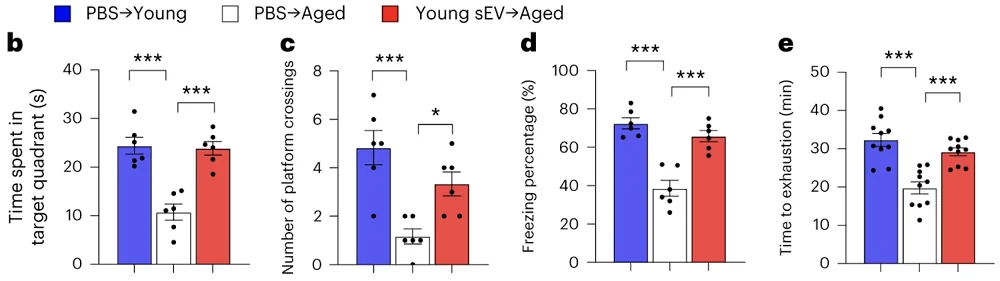

All of this led to clear cognitive and physical improvements. In the Morris water maze test, which assesses learning and memory, non-treated aged mice performed much worse than young controls, but this deficiency was almost completely reversed by the sEV treatment. The same happened in the treadmill endurance test, in which non-treated aged mice clocked a much shorter time to exhaustion, but the treated old animals kept pace with young controls.

Notably, the researchers also tried injecting aged mice with sEVs taken from other aged mice, but this failed to ameliorate any age-related deficiencies. When young mice were injected with sEVs from old mice, they experienced physical and cognitive decline, which is in line with previous research on heterochronic parabiosis.

Human EVs work in mice, and maybe vice versa

Digging deeper into the effects of the treatment, the researchers found that, even when administered for only two weeks, it lowered senescent cell burden and brought down reactive oxygen species (ROS) in multiple tissues to levels comparable with young controls. Similar reductions were observed in the levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and lipofuscin. Both are harmful compounds, the accumulation of which is associated with aging phenotypes.

Proteomic analysis of several tissues revealed that sEVs exerted a wide-ranging effect, most of which are related to mitochondrial dysfunction, epigenetic alterations, and genomic instability, all of which are known hallmarks of aging. The researchers found that in hippocampus and muscle, the treatment largely restored markers of mitochondrial health, including ATP production, DNA content, quantity, and morphology.

Since, according to the authors, “the biological activity of sEVs exhibits little to no species specificity”, they tried injecting old mice with sEVs derived from the blood of young humans, recapitulating many of the benefits observed in previous experiments. If the reverse is beneficial, this might solve the problem of EV supply for humans.

Literature

[1] Chen, X., Luo, Y., Zhu, Q., Zhang, J., Huang, H., Kan, Y., … & Chen, X. (2024). Small extracellular vesicles from young plasma reverse age-related functional declines by improving mitochondrial energy metabolism. Nature Aging, 1-25.

[2] Ashapkin, V. V., Kutueva, L. I., & Vanyushin, B. F. (2020). The effects of parabiosis on aging and age-related diseases. Reviews on New Drug Targets in Age-Related Disorders, 107-122.

[3] Grigorian Shamagian, L., Rogers, R. G., Luther, K., Angert, D., Echavez, A., Liu, W., … & Marbán, E. (2023). Rejuvenating effects of young extracellular vesicles in aged rats and in cellular models of human senescence. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 12240.