The link between inflammation, cellular senescence, aging, and cancer is a complex relationship, but a new study sheds light on how these four interact.

The light and dark side of inflammation and cellular senescence

Cellular senescence is a protective mechanism that helps us to stay healthy and avoid cancer by removing damaged and aged cells from the cell cycle while preventing them from creating damaged copies of themselves. Senescent cells are disposed of via a self-destruct process known as apoptosis.

However, cellular senescence has a dark side. As we age, the immune system slows down, becomes dysfunctional, and ceases to remove senescent cells, allowing them to accumulate.

The accumulation of senescent cells in aged tissues is a hallmark of aging and one of the processes that causes us to age[1]. As senescent cells build up, they trigger the immune system to generate excessive inflammation, which, in turn, impairs healthy tissue regeneration and drives the aging process ever faster.

This contributes to the smoldering and chronic age-related inflammation known as “inflammaging”. Other sources of inflammaging include microbial burden, cell debris and protein crosslinking. This chronic inflammation contributes to age-related diseases, including cancer, heart disease, and neurodegeneration.

The focus of current research efforts is to find ways to periodically remove senescent cells from the body using senolytic therapies or to reduce inflammation by manipulating the immune response.

Chromatin leaking leads to inflammation

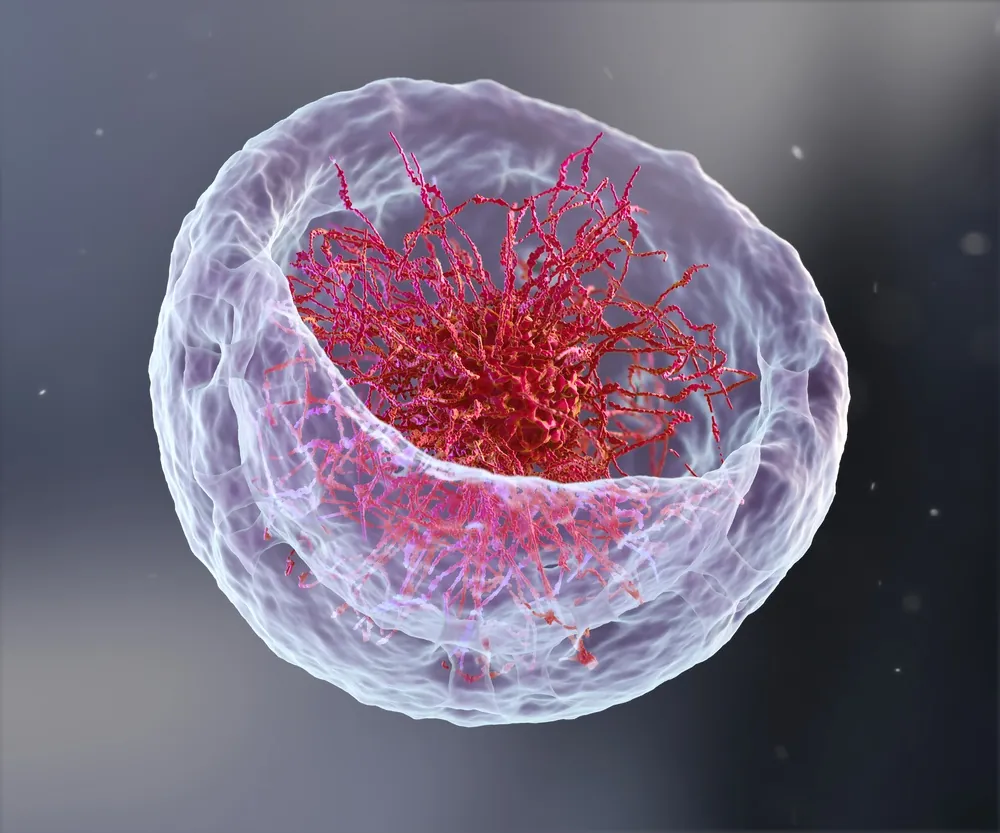

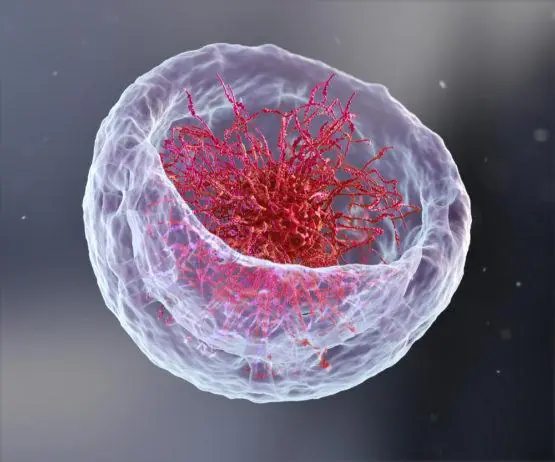

A new study by researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania found that chromatin – a structure in the cell nucleus where genes are housed – can become misplaced[2]. The traditional view is that chromatin as a cell component remains within the nucleus in order to regulate gene expression. However, the team found that there were misplaced chromatin fragments outside the nucleus that had been pinched off from nuclei present in senescent cells.

This misplaced chromatin causes a DNA-sensing pathway called cGAS-STING to become activated in its presence. The cGAS-STING pathway is based outside the nucleus and is known for its ability to combat microbial invasion from bacteria and viruses. It appears that in the case of cell senescence due to aging, the chromatin leaks outside the nucleus and triggers the cGAS-STING pathway, which reacts to this the same way it does to microbial infection. The leaking chromatin triggers an “alarm signal”, leading to inflammation.

Inducing short-term inflammation is useful in fighting infections and preventing cancers from developing; the problem begins when that inflammation becomes chronic, such as in aging. It leads to loss of tissue repair and ultimately can even help cancer spread.

The researchers used cellular stressors, such as DNA-damaging agents, activated oncogenes, and regular aging cells, to set off the alarm signal. They found that cells responded by shutting down and entering cellular senescence and calling the immune system to dispose of them. This depends on the immune system working properly, and while it is designed to clear away senescent cells, if uncontrolled, it can do more harm than good.

Sounding the alarm

The team observed that when mice with disabled cGAS-STING alarm pathways are exposed to cancer-inducing stressors, their cells do not summon the immune system for help. This is a problem because those damaged cells lead to the formation of tumors.

In normal mice exposed to stressors that induce aging, the accumulation of senescent cells causes a continual call for the immune system, leading to an excessive immune response and chronic, long-term inflammation. This then induces tissue damage, failure of tissue repair and premature aging.

Months after receiving stressors, the normal mice with an active alarm system showed masses of grey hair, a sign of aging in mammals, including humans. In contrast to this, mice lacking the alarm system had normal black hair, which shows exactly what the light and dark sides of cellular senescence are.

The researchers are now searching for molecules that target the always-on cGAS-STING alarm pathway in the hope of finding ways to manipulate the inflammatory response.

Conclusion

Science is steadily unraveling the exact mechanisms behind cellular senescence and how it contributes to chronic inflammation and aging. Of the two approaches to dealing with senescent cell accumulation, the removal of them seems the more direct approach over attempting to mediate the inflammation by tweaking various pathways, as these researchers are attempting to do.

While we find out more about how this complex interaction plays out, there are human trials for senolytics launching this year, and some studies are already in progress in some cases. In our view, removing the root of the problem seems to to be the more practical approach than modulating the signals from senescent cells without actually removing them.

Literature

[1] López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., & Kroemer, G. (2013). The hallmarks of aging. Cell, 153(6), 1194-1217.

[2] Dou, Z., Ghosh,K.,Grazia, M. et al. Cytoplasmic chromatin triggers inflammation in senescence and cancer. Nature (2017) doi:10.1038/nature24050.