In the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, Dr. Jesse Poganik and Prof. Vadim Gladyshev of Harvard Medical School have presented an opinion proposing a consensus understanding of aging.

A problem of focus and funding

The authors lament a lack of focus and funding in the field of gerontology, noting that a full 60% of funding for the National Institute on Aging is devoted to Alzheimer’s disease rather than aging as a whole. They note that there is no consensus on what is actually being studied, with “aging” lacking any generally accepted definition, and hold that this is a key reason behind why there is so little funding for interventions meant to tackle aging.

They also note the perennial problem of hucksters selling unproven products as “anti-aging” cures and treatments and note that the field must be unified in rejecting unproven claims. They hold that a broadly accepted definition of aging will help in pushing this sort of thing away from credible science.

Does an ‘essence of aging’ exist?

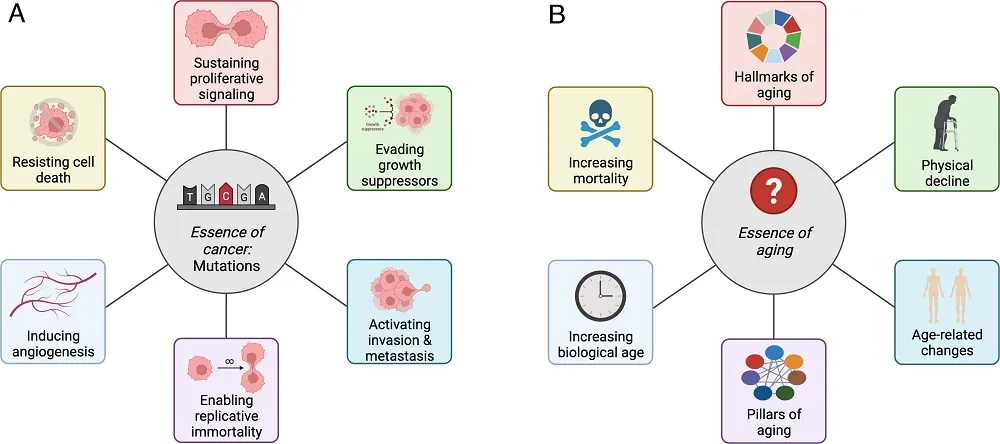

This argument includes statements that there is an “underlying, explanatory feature that leads to the others” and that there is a “single essence” that can be distilled. These authors present an analogy with cancer, with “mutations” being the central, defining aspect of cancer.

While mutations are the driving force behind cancer, addressing mutations as a whole is not where oncologists have found success in finding treatments that are more effective than chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Instead, clinical success on that front has involved focusing on the specific biological mechanisms involved in different cancer types [1]. There are highly effective treatments for specific cancers; a broad cure for every type of cancer is not on the horizon.

Aging is even more complex. Mutations, for example, are included in genomic instability, which is just one of the hallmarks of aging. Researchers have consistently found that these hallmarks intertwine and act upon one another, but sometimes there are no direct links; for example, epigenetic clocks are not affected by all hallmarks of aging. The proportional effect of the components of aging also varies by the individual person [2]. Evidence for the existence of a single source of all of these various hallmarks has not been found – at least not a source that can be effectively targeted.

If a broad ‘essence of aging’ can be said to exist, it is likely to be something as generic as ‘damage over time’ or perhaps ‘entropy’ (and it is fortunate for us that the Second Law of Thermodynamics only applies to closed systems). However, things like ‘damage’ and ‘entropy’ are not useful as clinical targets. Programmatic causes of age-related diseases are likely to exist as well, whether these programs were activated as a response to damage or existed since conception. “Programmatic causes”, as a whole, are also not a valuable target unless each of them can be identified and dealt with.

To borrow Dr. Aubrey de Grey’s original analogy of fixing a car, the car’s various parts may have sustained damage over time, but they did not sustain the same kinds of damage, nor can they all be repaired in the same way. Similarly, while many of our various bodily tissues share ways in which they are sustaining damage, there are differences, and replacing our parts is considerably more difficult than replacing a car’s.

Implications for collaborative research

If an agreed-upon target to study is identified and understood, powerful collaborations, particularly those with experts in complementary fields, may be more readily established.

While the authors are wholly correct in identifying the need for collaboration, if we accept aging as a multifarious collection of intertwining, overlapping, and interacting processes that need not share a single source, there is not one broad target worthy of collaborative study. Instead, multiple targets, each of which may be specific to the field and subfield being collaborated with, would be pinpointed in order to engage in research that leads to clinical trials.

Ideally, in such a collaborative environment, “because they’re older” would be less of an acceptable answer when determining why older people have worse prognoses. “Exactly how and why are they older, and what can we do about it?” would be the thing to investigate in each case.

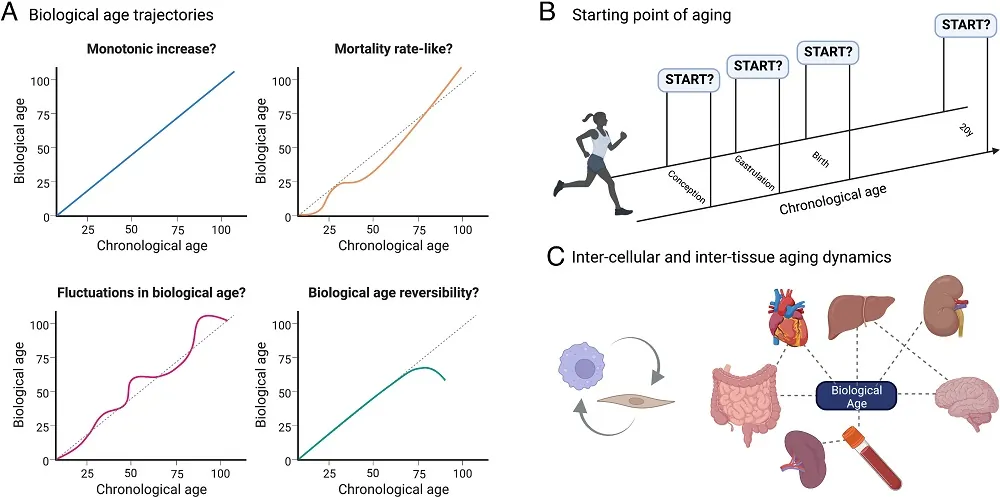

Similarly, the answers to the questions presented here may all be the same: “That depends on which specific process of aging you are talking about.” For example, there is the question of when aging begins. While the genome is vulnerable to damage from conception, we begin life in the womb as embryonic, pluripotent stem cells and other aspects of aging do not become a factor until far later.

Even something as broad as a whole-body epigenetic intervention is unlikely to fix everything. We recently reported on Dr. David Sinclair’s work on accomplishing epigenetic age reversal with small molecules. Even if such a treatment were to reset the epigenetic clocks of every last one of our cells, which would be a game-changing and very welcome development with tremendous downstream benefits, there is no guarantee that such a treatment would remove artery-clogging 7-ketocholesterol, and it may or may not have any impact on the gradual amyloidosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Difficult, but necessary

“How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.” Understanding specific biological processes is, of course, difficult, and every single one of these ‘bites’ is the result of painstakingly lengthy research. Even if there is a broadly agreed-upon definition of aging, this situation is unlikely to change, and there are few easy answers. However, to have results that pass clinical trials in human beings and ultimately make people live far longer lives, the complexity and difficulty of conquering aging, of slaying this particular Dragon-Tyrant, must be tackled head-on, in all its various forms.

Therefore, if we are to successfully combat the various processes that are killing us, substantial resources and funding must be devoted to each of the many, many tasks involved.

Literature

[1] Kumar, M., Nagpal, R., Hemalatha, R., Verma, V., Kumar, A., Singh, S., … & Yadav, H. (2012). Targeted cancer therapies: the future of cancer treatment. Acta Biomed, 83(3), 220-233.

[2] Ahadi, S., Zhou, W., Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose, S. M., Sailani, M. R., Contrepois, K., Avina, M., … & Snyder, M. (2020). Personal aging markers and ageotypes revealed by deep longitudinal profiling. Nature Medicine, 26(1), 83-90.