Recent research has contributed to the growing body of evidence regarding social isolation, loneliness, and biological aging [1].

Social isolation is not generally screened for

During doctor visits, patients are often screened for many physical conditions. However, screening for social isolation in the clinic is not as common as it should be, despite the evidence linking social isolation and physical health.

Recent research has linked social isolation to poor mental health [2], high blood pressure [3], poor control of diabetes mellitus [4], higher medical expenditure, more hospitalization rates [5], and higher mortality rates [6].

The authors emphasize that, despite this strong evidence on the deleterious impact of social isolation on one’s health, the understanding of the impact of social isolation on biological age, which is a better estimate of a person’s overall health and well-being, is limited. Therefore, the authors decided to investigate it.

AI-based biological cardiac age

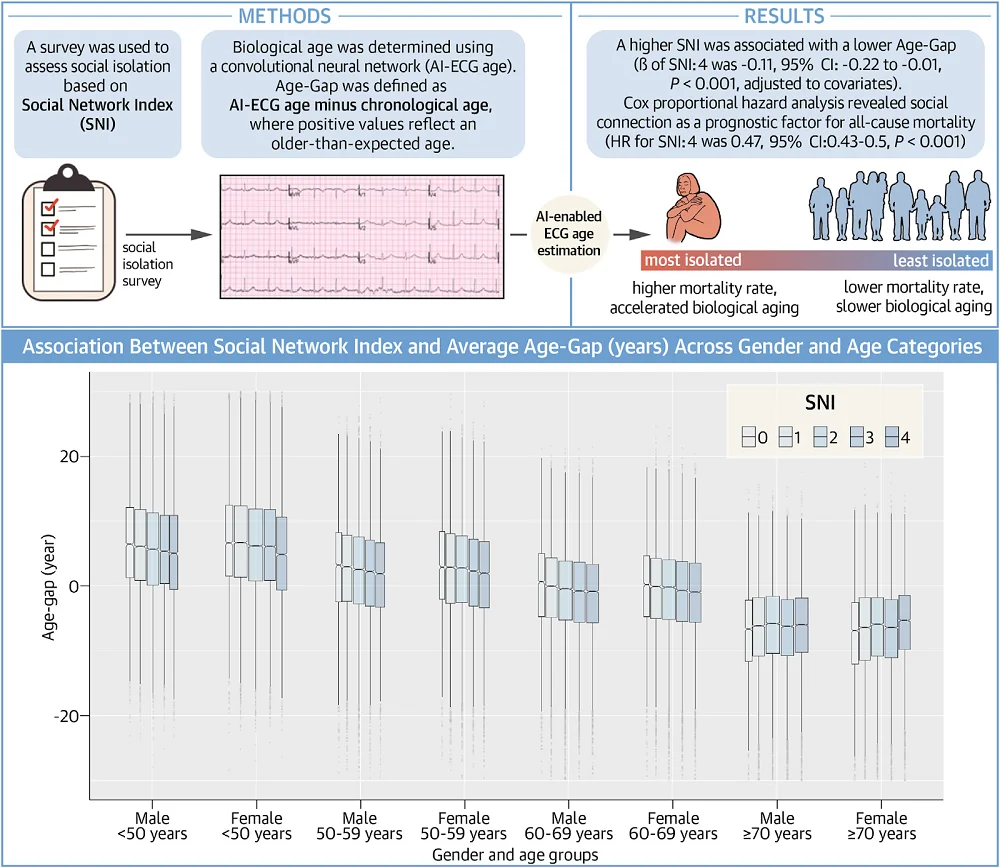

The study population included 280,324 Mayo Clinic patients with a mean chronological age of 59.8, who visited the clinic for outpatient visits between 2019 and 2022 and responded to a survey on the topic of social isolation. The researchers used a previously designed multiple-choice survey based on the Social Network Index, which ranged from 0 for the most isolated individuals to 4 for the least isolated.

Participants had to be at least 18 years old and have a 12-lead electrocardiogram, which records the electrical activity of the heart, within one year of completing these surveys to be included in the study.

Those ECGs were used to assess biological aging. Specifically, the authors used previously developed artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiography (AI-ECG). These results were then subtracted by their chronological age to get an Age-Gap value. A positive Age-Gap suggests accelerated aging, while a negative one suggests that it has been slowed down [7]. The mean Age-Gap of study participants was -0.2.

More socializing, slower aging

A higher survey score, which indicates less social isolation, was associated with a lower Age-Gap value, meaning that social isolation is associated with more rapid aging. The results showed differences among age groups, with social isolation impacting younger patients more.

The researchers followed up on the study cohort for a median of 24 months. During that time, 13,764 (4.9%) of the study participants died. Among the people who died, many suffered from hypertension (48.6%), hyperlipidemia (33.9%), and chronic kidney disease (24.8%) and were mostly older than the average participant.

An analysis revealed that social isolation and mortality were significantly associated. Individuals scoring higher on the survey (less isolated) experienced lower mortality risk. The authors point out that their results are in agreement with previous research linking social isolation with increased risk of multiple diseases, health conditions, and mortality.

Social isolation and health connections

The authors discussed the “bidirectional relationship between social isolation and chronic illnesses” [8, 9]. Previous literature shows that social isolation leads to increased cardiovascular event risk. On the other hand, suffering from chronic medical conditions makes people more likely to experience social isolation [8, 10].

The authors also discussed mechanisms that can possibly underline the association between social isolation and accelerated aging. They listed systemic inflammation and the endocrine

system as the two processes that might play a big role in this connection. They further explained that overactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis resulting from social isolation can lead to hypertension and accelerated atherosclerosis [11, 12]. On the other hand, social isolation has been shown to upregulate proinflammatory genes [13], leading to oxidative stress in vascular tissues and atherosclerosis [14,15].

Social isolation can also influence health through behavioral choices. For example, “social isolation is associated with a higher likelihood of health-risk behaviors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity” [16-18] and “poor medication adherence” [19].

Incorporating social isolation screening and helping to combat it can have a direct impact on people’s health, as a meta-analysis of 87 randomized control trials showed that support from family or groups “was associated with a 20% higher survival rate and a 29% higher likelihood of longer survival compared to standard care” [20].

The authors list a few limitations of this research. First, their study doesn’t fully represent the general population in terms of racial groups, and there is a risk of selection bias since the population was self-selected and included patients of the Mayo Clinic. Further limitations pertain to the model’s ability to estimate the patient’s biological age. The authors believe that their algorithms could be improved and note that their statistical analysis could increase the possibility of false positives.

This large population cohort demonstrated the independent association of social isolation with accelerated aging and a higher risk of mortality, even after controlling for demographic and clinical comorbidities.

Literature

[1] Ito, S., Cohen-Shelly, M., Attia, Z. I., Lee, E., Friedman, P. A., Nkomo, V. T., Michelena, H. I., Noseworthy, P. A., Lopez-Jimenez, F., & Oh, J. K. (2023). Correlation between artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiogram and echocardiographic features in aortic stenosis. European heart journal. Digital health, 4(3), 196–206.

[2] Mann, F., Wang, J., Pearce, E., Ma, R., Schlief, M., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ikhtabi, S., & Johnson, S. (2022). Loneliness and the onset of new mental health problems in the general population. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 57(11), 2161–2178.

[3] Hawkley, L. C., Thisted, R. A., Masi, C. M., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and aging, 25(1), 132–141.

[4] Ford, K. J., & Robitaille, A. (2023). How sweet is your love? Disentangling the role of marital status and quality on average glycemic levels among adults 50 years and older in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMJ open diabetes research & care, 11(1), e003080.

[5] Holt-Lunstad, J., & Perissinotto, C. (2023). Social Isolation and Loneliness as Medical Issues. The New England journal of medicine, 388(3), 193–195.

[6] Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on psychological science : a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237.

[7] Attia, Z. I., Friedman, P. A., Noseworthy, P. A., Lopez-Jimenez, F., Ladewig, D. J., Satam, G., Pellikka, P. A., Munger, T. M., Asirvatham, S. J., Scott, C. G., Carter, R. E., & Kapa, S. (2019). Age and Sex Estimation Using Artificial Intelligence From Standard 12-Lead ECGs. Circulation. Arrhythmia and electrophysiology, 12(9), e007284.

[8] Christiansen, J., Lund, R., Qualter, P., Andersen, C. M., Pedersen, S. S., & Lasgaard, M. (2021). Loneliness, Social Isolation, and Chronic Disease Outcomes. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 55(3), 203–215.

[9] Xu, X., Mishra, G. D., Holt-Lunstad, J., & Jones, M. (2023). Social relationship satisfaction and accumulation of chronic conditions and multimorbidity: a national cohort of Australian women. General psychiatry, 36(1), e100925.

[10] Barlow, M. A., Liu, S. Y., & Wrosch, C. (2015). Chronic illness and loneliness in older adulthood: The role of self-protective control strategies. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 34(8), 870–879.

[11] Burford, N. G., Webster, N. A., & Cruz-Topete, D. (2017). Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Modulation of Glucocorticoids in the Cardiovascular System. International journal of molecular sciences, 18(10), 2150.

[12] Yang, S., & Zhang, L. (2004). Glucocorticoids and vascular reactivity. Current vascular pharmacology, 2(1), 1–12.

[13] Powell, N. D., Sloan, E. K., Bailey, M. T., Arevalo, J. M., Miller, G. E., Chen, E., Kobor, M. S., Reader, B. F., Sheridan, J. F., & Cole, S. W. (2013). Social stress up-regulates inflammatory gene expression in the leukocyte transcriptome via β-adrenergic induction of myelopoiesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(41), 16574–16579.

[14] Siegrist, J., & Sies, H. (2017). Disturbed Redox Homeostasis in Oxidative Distress: A Molecular Link From Chronic Psychosocial Work Stress to Coronary Heart Disease?. Circulation research, 121(2), 103–105.

[15] Black, C. N., Bot, M., Révész, D., Scheffer, P. G., & Penninx, B. (2017). The association between three major physiological stress systems and oxidative DNA and lipid damage. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 80, 56–66.

[16] Lauder, W., Mummery, K., Jones, M., & Caperchione, C. (2006). A comparison of health behaviours in lonely and non-lonely populations. Psychology, health & medicine, 11(2), 233–245.

[17] Locher, J. L., Ritchie, C. S., Roth, D. L., Baker, P. S., Bodner, E. V., & Allman, R. M. (2005). Social isolation, support, and capital and nutritional risk in an older sample: ethnic and gender differences. Social science & medicine (1982), 60(4), 747–761.

[18] Hawkley, L. C., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2009). Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: cross-sectional & longitudinal analyses. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 28(3), 354–363.

[19] Lu, J., Zhang, N., Mao, D., Wang, Y., & Wang, X. (2020). How social isolation and loneliness effect medication adherence among elderly with chronic diseases: An integrated theory and validated cross-sectional study. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 90, 104154.

[20] Smith, T. B., Workman, C., Andrews, C., Barton, B., Cook, M., Layton, R., Morrey, A., Petersen, D., & Holt-Lunstad, J. (2021). Effects of psychosocial support interventions on survival in inpatient and outpatient healthcare settings: A meta-analysis of 106 randomized controlled trials. PLoS medicine, 18(5), e1003595.