Moderate Beer Consumption Produces Benefits in Mice

- Not all beers have the same effects.

- Artificially aged male mice were given original, IPA, and stout beers, which had somewhat different effects.

- Not all of the effects were attributed to the alcohol content.

- There were benefits for both the gut microbiome and oxidative stress.

Scientists have given three types of beer to artificially aged male mice and recorded numerous beneficial effects, including improvements in microbiome diversity and lipid profiles [1].

Can alcohol be healthy?

While it is firmly established that excessive alcohol consumption negatively impacts health, debates around moderate consumption are still ongoing. Some researchers suggest that the healthy level of alcohol consumption is zero [2], while others claim that the benefits outweigh the risks [3]. To complicate things further, alcohol comes in many forms, and the type seems to matter a lot. This is not surprising, since alcoholic beverages are made from plants, which contain many biologically active substances.

A lot of our knowledge about the effects of alcohol on human health comes from epidemiological studies, which can only establish correlations between levels of consumption and health outcomes and not causal relationships. Such studies are notoriously noisy and unreliable and cannot provide insight into the mechanisms of action.

A team of Chinese researchers from Qingdao Marine Biomedical Research Institute and the State Key Laboratory of Biological Fermentation Engineering of Beer at Tsingtao Brewery (note the industry connection) set out to close some of those gaps by getting mice drunk. To be precise, the animals were given small doses of beer roughly equivalent to 700 milliliters per week for humans.

To study the effects of the beverage on an aged organism, the mice were treated with D-galactose, a compound that induces aging-like phenotypes via increased production of reactive oxygen species and advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which quickly leads to weaker antioxidant defenses, liver/kidney strain, and a disrupted gut microbiome.

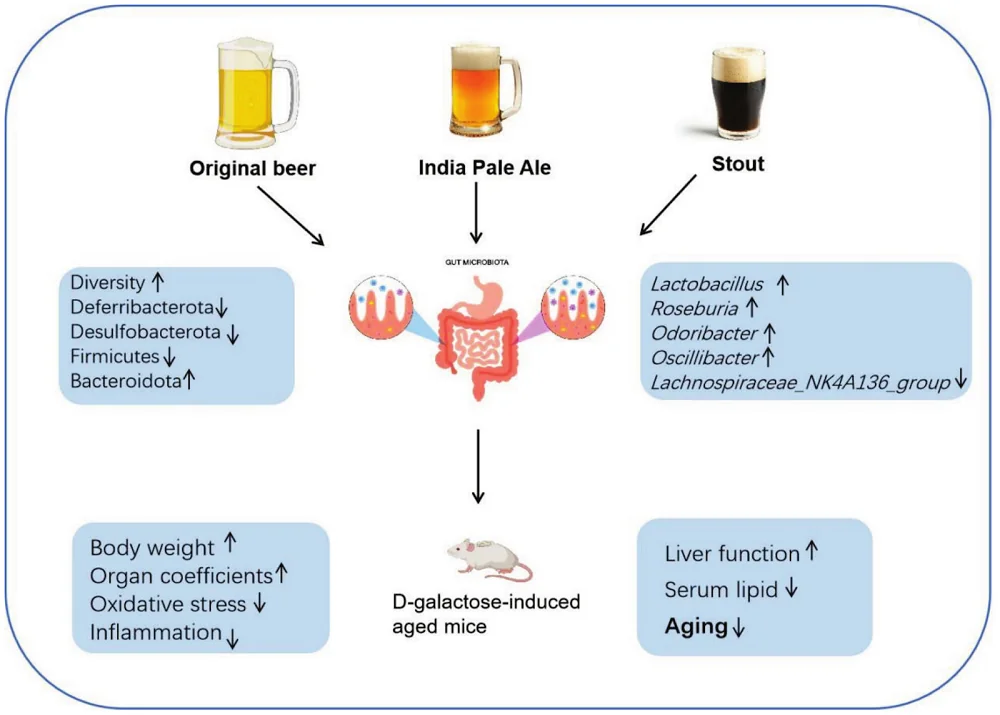

For four weeks, the artificially aged mice were given one of the three types of beer that the researchers obtained from the Tsingtao Brewery lab: original, IPA, and stout. The first one was basically an unfiltered pale lager, 5.42% alcohol by volume (ABV). The IPA and the stout packed a bit more punch: 5.83% and 7.54%, respectively.

All three beers mitigated the oxidative stress induced by D-galactose. Stout showed the strongest antioxidant effect overall, increasing the levels of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase and lowering malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of oxidative damage to fats in membranes (lipid peroxidation). Original beer most clearly improved glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), the cell’s primary antioxidant.

All three beers also produced anti-inflammatory effects. The levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 were reduced by IPA and stout. Original and stout lowered the levels of another pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-15. Finally, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), another marker of inflammation, was notably reduced by IPA. The researchers, however, suggest that the anti-inflammatory effects might be downstream from the antioxidative ones.

The team went on to study kidney and liver function and histology. Alcohol is usually associated with liver damage, but in this study, beer actually improved things in the liver compared to artificially aged controls. Stout led to lower levels of the liver markers ALT and AKP (also known as ALP), IPA lowered only AKP, and the original beer reduced AST levels. All the beers rescued liver damage caused by D-galactose, although the original beer’s effect was the smallest among the three. Kidney injury from D-galactose was attenuated by all beers as well.

Just like natural aging, D-galactose caused the mice’s lipid profiles to worsen (dyslipidemia). Here, too, beer seemed to help. IPA shined by lowering the levels of harmful LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. Original and stout lowered both LDL and total cholesterol but did not significantly impact triglycerides.

Microbiome improvements

The researchers thoroughly explored the impact of beer on the microbiome. D-galactose decreased gut diversity and skewed the microbiome. Beer reversed many of these changes: diversity rebounded, as beneficial bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (Roseburia, Lactobacillus, Odoribacte) increased in numbers while potentially pro-inflammatory taxa (e.g., Colidextribacter) declined.

The unfiltered original beer showed the biggest diversity bump, IPA demonstrated the clearest rebalancing, and stout most strengthened Lactobacillus/SCFA producers. These shifts tracked with lower inflammatory signals and better antioxidant and lipid markers.

The researchers tentatively attribute the effects they discovered to various bioactive molecules in the three beers. For example, the unfiltered original beer might be more effective in restoring microbiome diversity due to the high content of live yeast. Stout performed best as an antioxidant and hepatoprotector, consistent with its higher polyphenol and melanoidin content from roasted malts. Finally, IPA excelled in anti-inflammation and lipid regulation, which may be attributed to the activity of bitter acids abundant in hops.

The study had several limitations, such as using only male mice, as aging processes and responses to therapies often differ by sex. Importantly, the researchers used an artificial model of aging in otherwise young mice, which obviously does not fully recapitulate natural aging in humans. Finally, due to its short duration, the study may be less relevant for lifelong consumption.

On the other hand, using three types of beers with different effects is a nice touch. The authors call for other researchers to adopt this approach due to the notable diversity within different types of alcohol (beer, wine, strong spirits).

Literature

[1] Fu, X., Wang, C., Yang, Z., Yu, J., Wang, J., Cao, W., … & Hou, H. (2025). Moderate Beer Consumption Ameliorated Aging‐Related Metabolic Disorders Induced by D‐Galactose in Mice via Modulating Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis. Food Science & Nutrition, 13(8), e70678.

[2] Griswold, M. G., Fullman, N., Hawley, C., Arian, N., Zimsen, S. R., Tymeson, H. D., … & Farioli, A. (2018). Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet, 392(10152), 1015-1035.

[3] Meister, K. A., Whelan, E. M., & Kava, R. (2000). The health effects of moderate alcohol intake in humans: an epidemiologic review. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 37(3), 261-296.