Today we will review one of the reasons we are thought to age: Telomere attrition. Telomeres are an often misunderstood topic but do seem to play an important role in aging and age-related diseases.

Telomere attrition is a double edged sword

Human physiology contains numerous functional redundancies, with multiple mechanisms to address and back up critical processes. This is clear in how cells divide. This process is important for growth, development, healing wounds, and preventing cancer [1-2].

Telomere attrition is one of several regulatory mechanisms that ensure that cells do not divide uncontrollably. This serves as a safety feature to prevent cancer but that comes at a cost.

While telomere loss helps prevent cancer, it also causes apoptosis or senescence. Apoptosis is when a cell self-destructs and is disposed of. Senescence is when a cell stops dividing permanently but remains at large. Ultimately both of these things reduce the body’s ability to function and its regenerative power.

The loss of the body’s ability to regenerate is a key factor in aging. Senescent cells build up and hurt the body’s ability to repair and renew tissues. Apoptosis also reduces the number of functional cells in the body [3]. This makes telomere attrition one of López-Otín’s four primary hallmarks of aging [4].

Telomere shortening is especially problematic in cells that divide frequently, including numerous immune, skin, intestine, and hair cells. After around 50 cell divisions, the telomeres become critically short. This point is called the Hayflick limit. At this point the cell either destroys itself or enters a senescent state [5-6].

It is in this way that telomere loss is a double edged sword. It both protects us by removing aged and potentially damaged cells, but it also harms us in the long-term.

Telomere loss influences other hallmarks of aging and disease

Telomere attrition interacts with the other original hallmarks of aging. This highlights that nothing exists in isolation when it comes to the biology of aging. The various reasons we age are all connecting directly or indirectly to each other.

As telomeres shorten, their protective abilities diminish, leading to increased chromosome end-to-end fusions, loss of genetic information, and genomic instability [7]. Short telomeres cause a lasting DNA damage response. This worsens genomic instability by activating repair pathways. These pathways can lead to mutations or changes in chromosome structure [8].

Telomere shortening is linked to changes in how DNA and proteins are organized. This affects chromatin, chromosome ends, and other genomic areas. As a result, gene expression patterns change, leading to epigenetic alterations. This influences the expression of genes involved in maintaining epigenetic marks, resulting in widespread epigenetic changes [9].

The persistent DNA damage response caused by short telomeres can activate stress response pathways. These include those that affect protein homeostasis. This loss of proteostasis results in the accumulation of misfolded or damaged proteins.

Cellular senescence caused by telomere shortening releases pro-inflammatory cytokines, proteases, and other factors. This inflammatory cocktail is called the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). These factors can disrupt proteostasis and lead to tissue dysfunction [10].

The cellular senescence induced by telomere attrition also leads to alterations in metabolic pathways. These include the nutrient-sensing pathways like mTOR, AMPK, and insulin/IGF-1. These can affect cellular growth and metabolism, contributing to aging. Senescent cells can also contribute to systemic insulin resistance through SASP and deregulated nutrient sensing [11].

Additionally, short telomeres can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction by increasing oxidative stress, further damaging telomeric DNA and other cellular components. Senescent cells induced by telomere attrition often exhibit impaired mitochondrial function, reducing cellular energy production and increasing reactive oxygen species [12].

The accumulation of senescent cells contributes to tissue degeneration and dysfunction [13-14]. In stem cells, telomere shortening limits their ability to proliferate and maintain tissue homeostasis. It drives stem cells into senescence, depletes the stem cell pool and impairs tissue repair. This ultimately leads to stem cell exhaustion [15].

Telomere shortening is linked to many age-related diseases

The shortening of telomeres causes many harmful effects that contribute to aging and age-related diseases. The number of diseases shown to be directly and indirectly driven by telomere attrition includes:

- Cardiovascular disease [16]

- Cancer [17]

- Neurodegenerative diseases [18]

- Diabetes [19]

- Arthritis [20]

Additionally, several specific diseases are characterized by telomere dysfunction, such as aplastic anemia [21] and dyskeratosis congenita [22]. Scientists from many fields are studying how telomere maintenance works. They want to find ways to slow or reverse telomere loss. This could help prevent cancer and other age-related diseases.

Telomeres, enzyme complexes, and signaling pathways

Telomere attrition happens when cells divide and is caused by the “end replication problem.” The cellular machinery that copies DNA cannot anchor itself while it copies the last building blocks of a DNA strand. As a result, it does not complete the process. This results in a progressive shortening of the chromosome’s telomeres each time the cell divides [23].

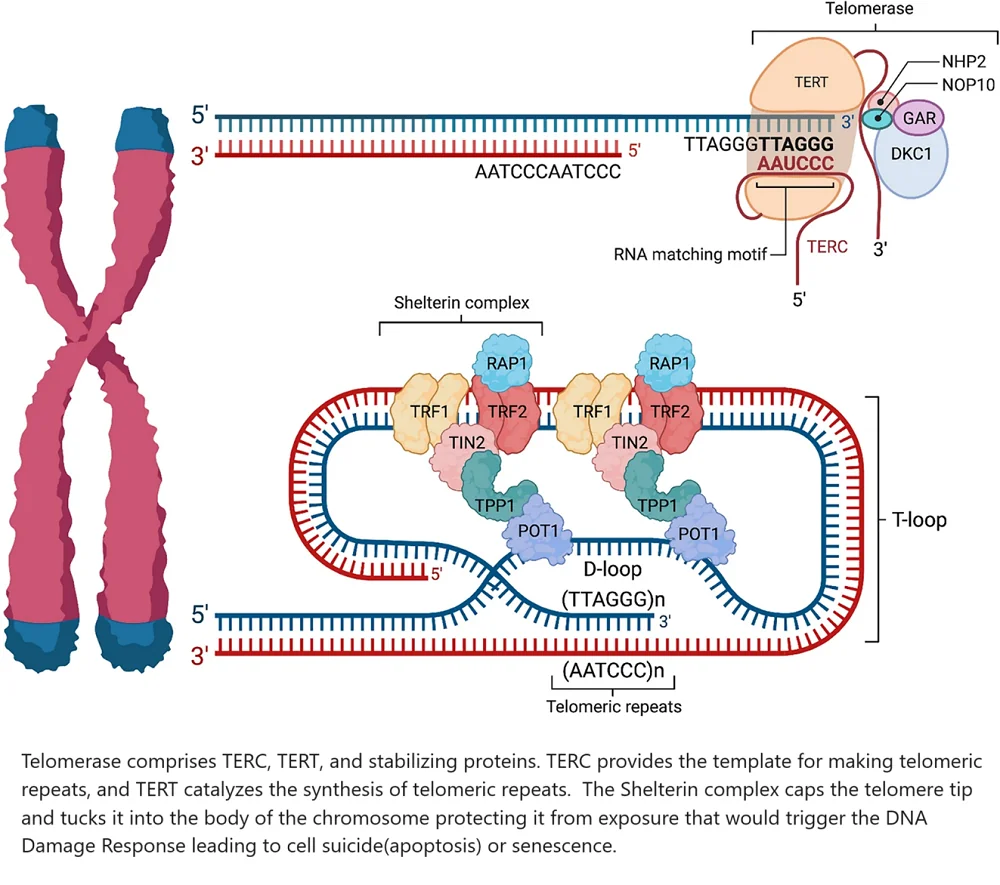

At each chromosome’s end is a long stretch of telomeric repeats of six-nucleotide sequences. Thousands of these repeats are added to the end of the chromosome. Then the tip is neatly looped and tucked in to form a protective cap [24].

Fortunately the body has mechanisms for extending telomeres. Telomerase is a critical enzyme that counters the erosion of telomeres. It does this by partially rebuilding them after each cell division occurs [25].

However, the rate at which this happens can vary greatly depending on individual genetic predisposition, exposure to oxidative damage, and other cellular stressors. A complex array of biomolecules regulates telomere length as the body simultaneously attempts to protect itself from cancer and optimize tissue regeneration capacity [26].

Two main enzyme complexes and several signaling pathways are important for controlling telomere length. These include the shelterin complex, which has TRF1, TRF2, TIN2, TPP1, POT1, and RAP1.

The telomerase complex includes TERT and TERC, along with stabilizing proteins like DKC1, NOP10, NHP2, and GAR. Key signaling pathways also play a role. These pathways are important for cell function. They include:

- The DNA damage response pathways (ATM and ATR)

- The p53 pathway

- The c-Myc pathway

- The MAPK/ERK pathway

- The TGF-β pathway

This forms the telomere maintenance and protection backbone [27]. When working correctly, these components and pathways ensure genomic stability, cellular longevity, and proper stress and damage response.

How the telomere maintenance system works

TERC harbors the RNA template needed to make the DNA sequence (TTAGGG) of the telomeric repeat. TERT binds to TERC to catalyze the synthesis of telomeric repeats [28].

The shelterin complex masks telomeres to prevent them from being treated as DNA damage. Without this feature in place, inappropriate DNA repair mechanisms would be triggered [29]. Shelterin’s subcomponents assume several roles. TRF1, TPP1, and POT1 block telomerase from gaining access to the telomere. This then binds to a single-stranded telomeric DNA [30].

TRF2 and RAP1 work together to prevent the activation of the DNA damage response. They do this by inhibiting the ATM kinase pathway, which is activated in response to DNA double-strand breaks [31].

TRF2 also tucks the single-stranded telomeric overhang into the body of the chromosome. This adds additional protection from the body’s DNA damage surveillance mechanisms [32]. This makes TIN2 the unsung hero that holds the shelterin complex together [33].

Regulation of telomerase in disease and stress

Telomerase regulation is critical for maintaining genomic stability, and its dysregulation is associated with various diseases, including cancer and age-related disorders [34].

TRF1 and TRF2 expression levels can be altered in cancers. Overexpression of TRF2 is frequently seen in cancer cells. This overexpression facilitates limitless replication by preventing telomere shortening [35].

Under stress conditions, such as oxidative stress, TRF1 and TRF2 can be upregulated to help protect telomeres from damage.

POT1 binds to single-stranded telomeric DNA and regulates telomerase access to the telomere. Mutations in POT1 can lead to dysregulated telomere elongation, contributing to tumorigenesis. During stress, altered binding of POT1 can lead to telomere instability and increased susceptibility to DNA damage [36].

TIN2 is a scaffolding protein stabilizing the shelterin complex. Mutations in TIN2 are connected to telomere syndromes. One example is dyskeratosis congenita, a condition that causes bone marrow failure and a higher risk of cancer [37]. TIN2 mutations can impair telomere maintenance under stress, exacerbating telomere shortening and dysfunction [38].

Relevant signaling pathways

ATM and ATR are proteins involved in the cellular response to DNA damage. They respond to double and single-strand DNA breaks, respectively. They are crucial in maintaining genomic stability and orchestrating the DNA damage response (DDR) pathways.

TRF2 inhibits ATM signaling at telomeres, preventing inappropriate DNA damage responses [39]. Dysregulation of ATM can lead to genomic instability and cancer [40].

ATR helps maintain telomere integrity under the stress of cell division. POT1 and TRF1 regulate ATR signaling at telomeres [41]. ATM and ATR can both activate the tumor suppressor p53. It can halt the cell cycle, cause cell death, or lead to aging when there is DNA damage [42].

P53 is mutated or inactivated in many cancers, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation. Telomere dysfunction can activate p53, linking telomere maintenance to tumor suppression. Under telomere stress, p53 is activated to initiate repair or trigger apoptosis, preventing the propagation of damaged cells [43].

c-Myc is an oncogene that can upregulate telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) expression, enhancing telomerase activity. Overexpression of c-Myc is common in cancers, leading to increased telomerase activity and enabling immortalization of cancer cells. Cellular stress can modulate c-Myc levels, influencing telomerase activity and telomere maintenance [44].

Conversely, TGF-beta [45] and P38/MAPK can decrease telomerase expression. P38/MAPK is a crucial regulator of the cellular stress response. This explains why people under stress often have abnormally shortened telomeres [46].

This is not a complete picture of cell signaling as it relates to telomere maintenance. However, it does touch on the primary cell signaling pathways that can influence telomere length.

Recent advances in telomere research

In 2024 a number of research publications showed the important roles of telomeres and telomerase. These findings focus on immune cells and the central nervous system. They highlight how these factors affect cellular aging and neurodegenerative diseases.

Several reviews addressed the limitations of using telomeres as biomarkers for chronological age; others explored the genetic factors influencing telomere length and longevity. Innovative techniques for precise telomere measurement were established; telomere dynamics on healthspan and space exploration were studied. Many studies were published to look at the links between telomere length, disease rates, and factors like smoking.

Finally, researchers looked into how telomere length changes with age and its link to aging. They also studied the potential of telomerase gene therapy for heart diseases. These findings underscore telomeres’ complex yet vital role in aging and disease, opening new avenues for therapeutic interventions. What follows are just a handful of research highlights from late 2023 and 2024.

In August 2023, Savage found that the baseline length of telomeres is set by both rare and common genetic traits from parents. The study showed that rare genetic changes in genes that help maintain telomeres can lead to very short telomeres. Some people may have telomeres shorter than the 1st percentile for their age. These conditions are called telomere biology disorders. They are connected to higher risks of several health issues. These include bone marrow failure, myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, and squamous cell carcinoma. The last type of cancer affects the head, neck, and anogenital areas.

On the other hand, rare genetic variants that cause long telomeres are linked to higher risks of other cancers. These include chronic lymphocytic leukemia and sarcoma [47]. This research raises concerns for potential telomere-lengthening therapies. The findings emphasize that having neither short nor long telomeres is crucial for minimizing cancer risk. The study concludes that maintaining a “just right” length of telomeres is essential for protecting against cancer [47].

In October 2023, Harley and his team researched telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT). They also looked at how telomere shortening impacts the central nervous system (CNS). They used CRISPR/Cas9 to create human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs). These cells had reduced telomerase function.

The researchers studied motor neurons and astrocytes. Their findings showed that telomere shortening caused signs of aging. These signs included more cellular senescence, inflammation, and DNA damage. This study showed that TERT is important for the growth of neural progenitor cells and the development of neurons. It offers a useful model for studying age-related brain diseases [48].

In November 2023, Chebly and his team studied aging. They focused on how human immune cells, especially T-cells, change a lot. These changes are significantly related to telomeres and telomerase. Their review highlighted the crucial roles of telomeres and telomerase in T-cell differentiation and aging. They noted a strong link between short telomeres, telomerase activation, and various T-cell malignancies. Their comprehensive review of existing literature emphasized the impact of telomere dynamics on health and age-related diseases [49].

In December 2023, Pepke reviewed telomeres as biomarkers for aging and their limitations in predicting chronological age. Despite a correlation between telomere length and age, significant individual variation influenced by genetic and environmental factors limits their predictive reliability. It warned against misleading efforts in wildlife conservation. It made clear that telomeres should not be used to estimate age [50].

In January 2024, Romero-Haro and his team conducted a study. They looked at how age influences the relationship between telomere length and aging. This research focused on the Japanese quail. They found that younger adults had shorter telomeres as they got older, but older adults did not show this trend. This study suggested that the costs and benefits of telomere maintenance change over a person’s life. This contributes to the mixed evidence on telomere dynamics and aging [51].

In February 2024, Abdel-Gabbar explored the role of telomeres and telomerase in age-related cardiovascular diseases. Short telomeres activate the DNA damage response (DDR), leading to cell cycle arrest in heart cells. This limited regenerative capacity is linked to conditions like heart failure. The study highlighted the potential of telomerase gene therapy to restore heart cell proliferation and treat cardiovascular diseases [52].

In March 2024, Torigoe and his team studied the FOXO3 gene variant rs2802292. They explored how it relates to telomere length, telomerase activity, and inflammation. They found that individuals with the longevity-associated G-allele of FOXO3 had longer telomeres and higher telomerase activity.

Older female carriers had lower levels of the pro-inflammatory IL-6. In contrast, older males had higher levels of the anti-inflammatory IL-10. This study suggested that FOXO3 promotes longevity through different mechanisms in men and women [53].

In April 2024, Karimian and his team developed telomere profiling, a method of precisely measuring telomere length. They found that telomere lengths vary significantly at the ends of chromosomes. These lengths are set at birth and stay the same as people get older. Examining telomere lengths in 147 individuals found consistent patterns in specific chromosome ends. Telomere profiling could enhance research and clinical approaches. It could provide detailed insights into telomere biology and its role in aging and disease [54].

Also in April 2024, Mason and his team discussed the importance of improving human health in an aging population. They focused on how telomere shortening is linked to aging and age-related diseases. This includes reduced fertility, dementia, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

They also discussed the lack of data on how long-duration space missions might affect telomeres and overall health. The NASA Twins Study has helped us understand these effects better. It could also guide future space missions and human life in extreme environments [55].

In the same month, Liang and his team used a DNA methylation-based telomere length (DNAmTL) estimator. They studied cancer rates and deaths in people with and without HIV [56]. They found that individuals with HIV had shorter DNAmTL, associated with higher cancer prevalence and increased mortality risk. Their findings underscored the impact of HIV infection, physiological frailty, and cancer on telomere length and overall health.

In May 2024, Hammami and colleagues studied the impact of cigarette smoke on telomere length and associated gene expression. They found that cigarette smoke extracts reduced the activity of telomere-stabilizing genes TRF2 and POT1. These extracts raised the levels of hTERT. hTERT is a part of telomerase that is connected to cancer. They also increased ISG15, which is an inflammatory protein.

Their research showed that smokers had higher levels of these markers in lung tissue and blood samples. This suggests that smoking accelerates telomere shortening and contributes to inflammation and cancer development [57].

No doubt there will be much more research focused on telomeres in the coming years. It is also possible that therapies focused on safely restoring lost telomeres might be developed.

Literature

[1] Kitano, H. Biological Robustness. Nature Reviews Genetics 2004 5:11 2004, 5, 826–837.

[2] Matthews, H.K.; Bertoli, C.; de Bruin, R.A.M. Cell Cycle Control in Cancer. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2021 23:1 2021, 23, 74–88.

[3] Lin, J.; Epel, E. Stress and Telomere Shortening: Insights from Cellular Mechanisms. Aging Res Rev 2022, 73, 101507..

[4] López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of Aging: An Expanding Universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278.

[5] Hayflick, L. The Limited in Vitro Lifetime of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res 1965, 37, 614–636..

[6] Faragher, R.G.A. The Relationship Between Cell Turnover and Tissue Aging. Aging of the Organs and Systems 2003, 1–28.

[7] Callén, E.; Surrallés, J. Telomere Dysfunction in Genome Instability Syndromes. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 2004, 567, 85–104.

[8] Reaper, P.M.; di Fagagna, A.; Jackson, S.P. Activation of the DNA Damage Response by Telomere Attrition: A Passage to Cellular Senescence. 2004..

[9] Adwan-Shekhidem, H.; Atzmon, G. The Epigenetic Regulation of Telomere Maintenance in Aging. Epigenetics of Aging and Longevity: Translational Epigenetics vol 4 2018, 119–136..

[10] Chakravarti, D.; LaBella, K.A.; DePinho, R.A. Telomeres: History, Health, and Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 2021, 184, 306–322.

[11] Carroll, B.; Korolchuk, V.I. Nutrient Sensing, Growth and Senescence. FEBS J 2018, 285, 1948–1958.

[12] Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, X.; Wang, F.; Geng, X. Telomere and Its Role in the Aging Pathways: Telomere Shortening, Cell Senescence and Mitochondria Dysfunction. Biogerontology 2018 20:1 2018, 20, 1–16.

[13] Muñoz-Espín, D.; Serrano, M. Cellular Senescence: From Physiology to Pathology. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2014 15:7 2014.

[14] Campisi, J.; D’Adda Di Fagagna, F. Cellular Senescence: When Bad Things Happen to Good Cells. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 729–740..

[15] Senescence of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (Review) Available online: https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/ijmm.2017.2912 (accessed on 30 May 2024).

[16] Fyhrquist, F.; Saijonmaa, O.; Strandberg, T. The Roles of Senescence and Telomere Shortening in Cardiovascular Disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2013 10:5 2013, 10, 274–283.

[17] Sampson, M.J.; Hughes, D.A. Chromosomal Telomere Attrition as a Mechanism for the Increased Risk of Epithelial Cancers and Senescent Phenotypes in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 1726–1731.

[18] Levstek, T.; Kozjek, E.; Dolžan, V.; Trebušak Podkrajšek, K. Telomere Attrition in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 556488.

[19] Iwasaki, K.; Abarca, C.; Aguayo-Mazzucato, C. Regulation of Cellular Senescence in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Diabetes Metab J 2023, 47, 441–453.

[20] Lee, Y.H.; Jung, J.H.; Seo, Y.H.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, S.J.; Ji, J.D.; Song, G.G. Association between Shortened Telomere Length and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Meta-Analysis. Lupus 2017, 26, 282–288.

[21] Ball, S.E.; Gibson, F.M.; Rizzo, S.; Tooze, J.A.; Marsh, J.C.W.; Gordon-Smith, E.C. Progressive Telomere Shortening in Aplastic Anemia. Blood 1998, 91, 3582–3592.

[22] Nelson, N.D.; Bertuch, A.A. Dyskeratosis Congenita as a Disorder of Telomere Maintenance. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2012, 730, 43–51.

[23] Bonnell, E.; Pasquier, E.; Wellinger, R.J. Telomere Replication: Solving Multiple End Replication Problems. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 668171.

[24] Wang, Y.; Patell, D.I. Solution Structure of the Human Telomeric Repeat d[AG3(T2AG3)3] G-Tetraplex.

[25] Collins, K.; Mitchell, J.R. Telomerase in the Human Organism. Oncogene 2002, 21, 564–579.

[26] Fernandes, S.G.; Dsouza, R.; Khattar, E. External Environmental Agents Influence Telomere Length and Telomerase Activity by Modulating Internal Cellular Processes: Implications in Human Aging. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2021, 85, 103633.

[27] Muoio, D.; Laspata, N.; Fouquerel, E. Functions of ADP-Ribose Transferases in the Maintenance of Telomere Integrity. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2022, 79.

[28] Nagpal, N.; Agarwal, S. Telomerase RNA Processing: Implications for Human Health and Disease. Stem Cells 2020, 38, 1532–1543.

[29] Mir, S.M.; Tehrani, S.S.; Goodarzi, G.; Jamalpoor, Z.; Asadi, J.; Khelghati, N.; Qujeq, D.; Maniati, M. Shelterin Complex at Telomeres: Implications in Ageing. Clin Interv Aging 2020, 15, 827–839.

[30] Kibe, T.; Osawa, G.A.; Keegan, C.E.; Lange, T. de Telomere Protection by TPP1 Is Mediated by POT1a and POT1b. Mol Cell Biol 2010, 30, 1059–1066.

[31] Eliˇ, E.; Janoušková, E.; Janouškov, J.; Janoušková, J.; Ně Casovácasov´casová, I.; Pavloušková, J.; Pavlouškov, P.; Pavloušková, P.; Zimmermann, M.; Hluch´y, M.; et al. Human Rap1 Modulates TRF2 Attraction to Telomeric DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, 2691–2700.

[32] Bianchi, A.; Smith, S.; Chong, L.; Elias, P.; De Lange, T. TRF1 Is a Dimer and Bends Telomeric DNA. EMBO J 1997, 16, 1785–1794.

[33] Khodadadi, E.; Mir, S.M.; Memar, M.Y.; Sadeghi, H.; Kashiri, M.; Faeghiniya, M.; Jamalpoor, Z.; Sheikh Arabi, M. Shelterin Complex at Telomeres: Roles in Cancers. Gene Rep 2021, 23, 101174.

[34] Saretzki, G. Role of Telomeres and Telomerase in Cancer and Aging. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, Vol. 24, Page 9932 2023, 24, 9932.

[35] Pal, D.; Sharma, U.; Singh, S.K.; Kakkar, N.; Prasad, R. Over-Expression of Telomere Binding Factors (TRF1 & TRF2) in Renal Cell Carcinoma and Their Inhibition by Using SiRNA Induce Apoptosis, Reduce Cell Proliferation and Migration Invitro. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0115651.

[36] Wu, Y.; Poulos, R.C.; Reddel, R.R. Role of POT1 in Human Cancer. Cancers 2020, Vol. 12, Page 2739 2020, 12, 2739.

[37] Yang, D.; He, Q.; Kim, H.; Ma, W.; Songyang, Z. TIN2 Protein Dyskeratosis Congenita Missense Mutants Are Defective in Association with Telomerase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 23022–23030.

[38] Schmutz, I.; Mensenkamp, A.R.; Takai, K.K.; Haadsma, M.; Spruijt, L.; De Voer, R.M.; Choo, S.S.; Lorbeer, F.K.; Van Grinsven, E.J.; Hockemeyer, D.; et al. Tinf2 Is a Haploinsufficient Tumor Suppressor That Limits Telomere Length. Elife 2020, 9, 1–20.

[39] Karlseder, J.; Hoke, K.; Mirzoeva, O.K.; Bakkenist, C.; Kastan, M.B.; Petrini, J.H.J.; De Lange, T. The Telomeric Protein TRF2 Binds the ATM Kinase and Can Inhibit the ATM-Dependent DNA Damage Response. PLoS Biol 2004, 2, e240.

[40] Abbas, T.; Keaton, M.A.; Dutta, A. Genomic Instability in Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013, 5, a012914.

[41] Loayza, D.; De Lange, T. POT1 as a Terminal Transducer of TRF1 Telomere Length Control. Nature 2003 423:6943 2003, 423, 1013–1018.

[42] Li, H.; Cao, Y.; Berndt, M.C.; Funder, J.W.; Liu, J.P. Molecular Interactions between Telomerase and the Tumor Suppressor Protein P53 in Vitro. Oncogene 1999 18:48 1999, 18, 6785–6794.

[43] Artandi, S.E.; Attardi, L.D. Pathways Connecting Telomeres and P53 in Senescence, Apoptosis, and Cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 331, 881–890.

[44] Wu, K.J.; Grandori, C.; Amacker, M.; Simon-Vermot, N.; Polack, A.; Lingner, J.; Dalla-Favera, R. Direct Activation of TERT Transcription by C-MYC. Nature Genetics 1999 21:2 1999, 21, 220–224.

[45] Lacerte, A.; Korah, J.; Roy, M.; Yang, X.J.; Lemay, S.; Lebrun, J.J. Transforming Growth Factor-β Inhibits Telomerase through SMAD3 and E2F Transcription Factors. Cell Signal 2008, 20, 50–59.

[46] Harada, G.; Neng, Q.; Fujiki, T.; Katakura, Y. Molecular Mechanisms for the P38-Induced Cellular Senescence in Normal Human Fibroblast. The Journal of Biochemistry 2014, 156, 283–290.

[47] Savage, S.A. Telomere Length and Cancer Risk: Finding Goldilocks. Biogerontology 2024, 25, 265–278.

[48] Harley, J.; Santosa, M.M.; Ng, C.Y.; Grinchuk, O. V.; Hor, J.H.; Liang, Y.; Lim, V.J.; Tee, W.W.; Ong, D.S.T.; Ng, S.Y. Telomere Shortening Induces Aging-Associated Phenotypes in HiPSC-Derived Neurons and Astrocytes. Biogerontology 2024, 25, 341–360.

[49] Chebly, A.; Khalil, C.; Kuzyk, A.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Chevret, E. T-Cell Lymphocytes’ Aging Clock: Telomeres, Telomerase and Aging. Biogerontology 2023 25:2 2023, 25, 279–288.

[50] Pepke, M.L. Telomere Length Is Not a Useful Tool for Chronological Age Estimation in Animals. BioEssays 2024, 46, 2300187.

[51] Romero-Haro, A.; Mulder, E.; Haussmann, M.F.; Tschirren, B. The Association between Age and Telomere Length Is Age-Dependent: Evidence for a Threshold Model of Telomere Length Maintenance. J Exp Zool A Ecol Integr Physiol 2024, 341, 338–344.

[52] Abdel-Gabbar, M.; Kordy, M.G.M. Telomere-Based Treatment Strategy of Cardiovascular Diseases: Imagination Comes to Reality. Genome Instability & Disease 2024 5:2 2024, 5, 61–75.

[53] Torigoe, T.H.; Willcox, D.C.; Shimabukuro, M.; Higa, M.; Gerschenson, M.; Andrukhiv, A.; Suzuki, M.; Morris, B.J.; Chen, R.; Gojanovich, G.S.; et al. Novel Protective Effect of the FOXO3 Longevity Genotype on Mechanisms of Cellular Aging in Okinawans. npj Aging 2024 10:1 2024, 10, 1–9.

[54] Karimian, K.; Groot, A.; Huso, V.; Kahidi, R.; Tan, K.T.; Sholes, S.; Keener, R.; McDyer, J.F.; Alder, J.K.; Li, H.; et al. Human Telomere Length Is Chromosome End-Specific and Conserved across Individuals. Science (1979) 2024, 384, 533–539.

[55] Mason, C.E.; Sierra, M.A.; Feng, H.J.; Bailey, S.M. Telomeres and Aging: On and off the Planet! Biogerontology 2024 25:2 2024, 25, 313–327.

[56] Liang, X.; Aouizerat, B.E.; So-Armah, K.; Cohen, M.H.; Marconi, V.C.; Xu, K.; Justice, A.C. DNA Methylation-Based Telomere Length Is Associated with HIV Infection, Physical Frailty, Cancer, and All-Cause Mortality. Aging Cell 2024, 00, e14174.

[57] Hammami, S.; Lizard, G.; Vejux, A.; Deb, S.; Berei, J.; Miliavski, E.; Khan, M.J.; Broder, T.J.; Akurugo, T.A.; Lund, C.; et al. The Effects of Smoking on Telomere Length, Induction of Oncogenic Stress, and Chronic Inflammatory Responses Leading to Aging. Cells 2024, Vol. 13, Page 884 2024, 13, 884.