When debating life extension, or debating in general, it may happen that participants commit logical fallacies—that is, their arguments contain logically invalid reasoning. In practice, this often means that people incorrectly come to certain conclusions that do not actually follow from the premises; if they appear to follow, it’s indeed because fallacious reasoning was used.

Logical fallacies can be tough to spot, both for the people committing them and for the people listening; rejuvenation advocates would therefore benefit from familiarizing themselves with common fallacies committed during debates about life extension so that they will detect them in other people’s arguments and avoid committing any themselves.

The following is a list of common logical fallacies that usually show up during life extension debates. It may be useful for your advocacy efforts, but bear in mind that the right way to go about rebutting fallacious reasoning is not simply pointing out “You committed a fallacy; your argument is invalid”; in fact, you’d better avoid mentioning the word “fallacy” altogether. What you are likely to get this way is simply a lot of eye-rolling; your message will probably not get across, and you will come across as an insufferable pedant, even if you’re right.

You may even meet people who don’t seem to think that a logical fallacy in their reasoning is such a big deal. Debating with this kind of person is probably a waste of time, but in general, people might be more receptive if you politely explain why their reasoning doesn’t work, providing different examples and avoiding a lecturing attitude at all costs.

Index

You can jump to specific fallacies by clicking any of these links; to jump back up here, click the “^ Back to index ^” link at the bottom of each fallacy.

Alleged Certainty

Aliases: assuming the conclusion

External sources: Logically Fallacious

Related cognitive biases: Illusory truth effect

Description

This fallacy consists of concluding something is true because “everybody knows” it is, which explains why the alias is assuming the conclusion; saying that “everybody knows X is true” implies a (not so) hidden assumption that X is true to begin with. So, this is basically like saying that X is true because it is—can’t argue with that logic, right? This makes the fallacy somewhat similar to circular reasoning (described here), since, in both cases, the person committing the fallacy is assuming what she was trying to prove in the first place, but circular reasoning is different in that you often have two separate statements used to back each other up:

A: “God exists!”

B: “How do you know?”

A: “Because it says so in my holy text.”

B: “How do you know your holy text is correct?”

A: “Because God wrote it.”

General examples

Typical examples, which incidentally are also related to life extension, are claims about pharmaceutical companies or overpopulation. It’s not at all uncommon to hear that Big Pharma is holding back the cure for cancer and who knows what else, because keeping people sick and producing more palliatives than actual cures may be more profitable; when you ask the proponents of this idea to prove it’s true, you may easily be told, “Oh, everybody knows it.” While profitability could easily be a motive for Big Pharma to play unfair, a possible motive is not a proof that this actually happens, and whether or not everybody knows it (or rather, everybody thinks that they know) is even less so.

However, as said, the fact that everybody knows something does not make that something true; hard data is needed to establish whether a pharmaceutical company is acting for its own interests against the patients’ best interests (and you certainly can’t draw universal conclusions in this regard about all pharmaceutical companies).

Occurrences in life extension

“Everybody knows” that there are too many people on this planet and therefore rejuvenation is a bad idea; “everybody knows” that life-saving treatments, such as rejuvenation, will always be only for the rich; and so on. Whether or not everybody actually knows these things doesn’t matter; what does matter is the evidence used to back them up. For example, overpopulation is not at all a black-and-white issue; whether we’re overpopulated depends on the metrics that are taken into account. For example, do we lack space, resources, or jobs, are we emitting too much carbon dioxide, and do the answers to these questions depend entirely on the number of people? This also involves the Earth’s carrying capacity, which is a variable, rather poorly defined number.

How to deal with this fallacy

While there are facts that probably everyone does know, such as the fact that the Earth is round, these can be backed up with evidence when necessary; whether or not “everybody knows” them doesn’t prove them.

The best way to counter this fallacy may be simply asking for evidence and pointing out that simply claiming that everyone knows something isn’t sufficient proof, especially if the topic is not at all uncontroversial.

Appeal to anger

Aliases: appeal to outrage, argumentum ad iram

External sources: Logically Fallacious

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

This fallacy attempts to justify an argument based solely on negative emotions. Typically, this involves rejecting an argument only because someone is outraged or enraged by it without any actual evidence against the argument having been presented; it can also be used as a smokescreen to hide the weaknesses of an argument.

General examples

A classic example is the refusal to even consider the possibility that differences in aptitudes and preferences between the sexes, even if absolutely benign, might exist, typically because of the assumption that the observation of such differences might conceal discriminatory intent. This usually causes outrage in many people, who refuse it precisely on the grounds that they find it outrageous, whether evidence supports it or not.

Another example would be the following situation: Your neighbor tells you that she thinks your son broke her window while playing ball in the yard, but you refuse to even listen to her because you’re outraged that she thinks such a thing of your son.

Occurrences in life extension

In the context of life extension, this fallacy is rarely committed alone; it usually hinges on other fallacies or weak arguments that are used as premises. For example, someone might be outraged that you worry about life extension when, allegedly, there are much worse problems than aging in the world, and he might use the supposed outrageousness of life extension to gloss over the fact that aging is a problem, whether or not worse problems than it exist.

Another example that works in the exact same way involves potential inequality of access to rejuvenation therapies. Claiming that rejuvenation would be only for the rich is a surefire way to outrage and anger people, instinctively pushing them to oppose life extension for the sake of preventing inequality. However, blinded by rage, people fail to realize that opposing or banning life extension wouldn’t improve, by one tiny bit, the lives of the people who supposedly would not have access to it whether it existed or not and that, ultimately, this is not a valid argument against it.

How to deal with this fallacy

If someone commits this fallacy, you should kindly point out that the way he feels about a statement or an idea is not what makes it true or false. Whether we’re outraged by something doesn’t mean that we can discount it. If necessary, you can also point out how being angry at something is likely to make people less prone to logical reasoning and less likely to notice the shortcomings of certain arguments or the strengths of others; however, be careful, because this observation has the potential to make people even angrier.

Aliases: argument from authority, ipse dixit, argumentum ad verecundiam

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

The infamous appeal to authority involves believing a claim solely because the person who made it is in a position of authority or prestige. The underlying assumption is that, by virtue of her status alone, this person must be right, either because she can’t make a mistake or is assumed to have verified the claim in question.

A variant of this fallacy, called the appeal to false authority, is committed when the person on whose authority you are relying isn’t competent in a relevant field—for example, believing a claim about economics made by a famous physicist simply because that person is a famous physicist constitutes an appeal to false authority because the field of expertise of the physicist isn’t relevant to economics and, therefore, is not an authority in that field.

General examples

Examples of this fallacy are abundant when people are trying to have their favorite beliefs prevail in a discussion among non-experts; for instance, you could claim that eating a cake a day is perfectly healthy because your cousin is a nutritionist and he said that it’s healthy. It seems unlikely that he might have, but even if he did, this doesn’t make the claim true; a lot of evidence would be required to clear refined carbs from the well-supported accusation of being a driver of obesity.

Occurrences in life extension

When discussing rejuvenation, the appeal to authority fallacy is sometimes observed when people say that rejuvenation isn’t possible or that some possible negative consequences of it are certain because an expert said so. The expert in question might well be right, but in order to establish it, his evidence must be examined to make sure that he isn’t genuinely mistaken or doesn’t have some other reason to make an unsubstantiated claim.

How to deal with this fallacy

Explain that everyone can make a mistake, no matter how smart, authoritative, or knowledgeable he may be. You don’t take for granted what Albert Einstein said because he was one of the greatest physicists of all time; his claims, too, need proof, and until said proof is presented and verified, you can’t say whether the claim is true or false.

It’s important to notice that relying on the opinion of experts isn’t always the same as appeal to authority; for example, we routinely trust our doctor when she prescribes us a drug. However, we’re not simply taking her word that she is a qualified doctor; the fact that she has other, satisfied patients and a valid license are some ways that we can know that our doctor is trustworthy. Additionally, she’s basing her diagnosis on tests and checkups that can be independently verified; if we’re not convinced of the diagnosis of our doctor, we can always turn to another one for a second opinion.

Appeal to motive

Aliases: argument from motives, appeal to personal interest

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

The fallacy of appeal to motive consists of dismissing an idea on the grounds of the motives of its proponent, sometimes even suggesting that, if the proponent of the idea might have a vested interest in proposing it, then this must necessarily be the reason why he did it in the first place. This is a form of ad hominem attack—attacking the proponent rather than the idea being proposed.

General examples

Anyone’s motives may well be debatable, but the idea may still be good; for example, a billionaire might write a large check to UNICEF only for the sake of publicity without really caring about helping children. You may argue that his motives are questionable, but the donation will still benefit many children in need.

Another example is being against a tax break because the politicians who voted for it might have done so for their own benefit—this might be the case, but this doesn’t mean that there can’t be valid reasons as well.

Occurrences in life extension

A typical life extension-related example is that of patient-funded clinical trials. At such an early stage, experimental rejuvenation therapies are indeed expensive, and governments may not be willing to pay for what seems like a moon shot. Thus, wealthy people willing to pay to try the therapies are effectively making it easier to test them.

Some people may argue that wealthy people are doing this not to help the research but for their own benefit; consequently, they feel outraged and despise the idea of patient-funded trials entirely, deeming it nothing but proof that rejuvenation is only for the rich.

However, regardless of the motives that push rich people to pay for these experimental treatments, the fact is that the treatments are experimental indeed; it’s as of yet unknown whether they’re even safe in humans, let alone if they yield any benefit. Effectively, these rich people are paying to be guinea pigs, even though they’re doing it for potential personal benefits rather than for the greater good.

Similarly, someone might think that life extension advocates are pushing to have aging cured only because they don’t want to die, not because they’re interested in reducing the suffering of the elderly. Whether this is the true motive depends on individual advocates, but it’s immaterial—whatever their reasons may be, their actions are helping to make rejuvenation a reality, which may, in turn, reduce the suffering of millions.

How to deal with this fallacy

Explain that anyone’s motives for endorsing an idea are irrelevant when assessing whether the idea is good or not. It may help if you explain that you too disagree with the motives of people who push life extension only for their own interest but that life extension is a worthy goal per se.

Appeal to nature

Aliases: argumentum ad naturam

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

The appeal to nature fallacy consists of implying that everything that is natural is better than everything that is not natural, and vice versa, or that natural equals good while unnatural equals bad. This fallacy is very much ingrained in the human mind, which is the reason why “100% natural ingredients” labels are on so many products on the shelves of supermarkets. This fallacy is not to be confused with the naturalistic fallacy.

General examples

In general, even the definition of “natural” can be difficult to agree upon, but broadly speaking, the most common interpretation is “that which is found in nature, without the need for human intervention”. Obviously, the strict belief in this fallacy has many hilarious and unsubtle problems: viruses, earthquakes, asteroid collisions, volcanic eruptions, cocaine, malaria, being eaten by a lion, and even radioactive decay are all perfectly natural things that can easily be extremely bad for you. Conversely, vaccines, anti-seismic buildings, contingency plans for asteroid impacts or volcano explosions, detoxification programs, cages for lions, and radiation shielding suits aren’t generally found in nature; yet, they are rather good for you in that they may well save your life.

Occurrences in life extension

In the context of life extension, you can expect to encounter this fallacy as the most classical of objections, the one and only “but aging is natural, while rejuvenation is not!” This fallacy is why people infer that aging is better or more desirable than using rejuvenative therapies to avoid it—which is not unlike saying that having cancer is better than using immunotherapy to cure it.

How to deal with this fallacy

The appeal to nature fallacy is easily countered with examples of undesirable yet perfectly natural things that we suffer from and desirable yet unnatural things that we use every day. Depending on how entrenched someone is, you can expect that person to resort to a double standard right after—”yes, but with aging, it’s different.” It is not. The bottom line is that naturalness is not a sufficient criterion to judge whether or not is something is good or desirable, regardless of what that thing may be.

Appeal to normality

Aliases: —

External sources: Logically Fallacious

Related cognitive biases: Status quo bias

Description

An appeal to normality consists of justifying something on the grounds that it is normal within socially accepted standards or that it is simply common. While the word “normal” is often used in the acceptation of “within acceptable ideal values” (e.g., normal blood sugar values are called that because they allow proper functioning of your body), it’s easy to slip up and assume that “normal” as in “commonly observed” implies that a thing is also good, desirable, or acceptable and, conversely, that everything that is not the norm is bad, undesirable, or unacceptable.

General examples

There’s a number of things that can be “normal” in a given context or certain circumstances, yet they are still bad. For example, even if most people are obese where you live, which makes obesity a norm, being obese is bad for you. Inferring that being obese is okay because most people are obese constitutes an appeal to normality. Similarly, it’s perfectly normal that many lives are lost during war, but that doesn’t make it good. It’s perfectly normal to break a few bones if a car runs you over, but that doesn’t mean it’s not something to worry about if it happens.

Occurrences in life extension

In the context of aging and life extension, someone might commit this fallacy by claiming that it’s normal to have high blood pressure, flaccid muscles, or poor eyesight in old age and, therefore, that there’s nothing wrong with it; similarly, as it is currently normal to die well before age 110, it’s easy to incorrectly infer that it’s good to die before age 110 and bad to live longer than that. Needless to say, having high blood pressure, etc, is bad for you whether you’re 10 or 100; the fact that high blood pressure is far more common at age 100 than age 10 doesn’t make it any less bad.

How to deal with this fallacy

“Normal” only refers to what is commonly observed in a given population or context; it says nothing about whether that thing is good, bad, desirable, or undesirable. You can get this message across by providing examples of things that are normal in a certain frame of reference and yet obviously bad—e.g., two centuries ago, it was perfectly normal that many lives were lost to infectious diseases, yet it was not good nor desirable. Beware—a double standard is likely to follow once you address this fallacy.

Appeal to probability

Aliases: appeal to possibility

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

A person commits this fallacy when concluding that something is true on the grounds that it is, or might be, possible. In other words, it boils down to believing that if something is possible, then it’s true.

General examples

Suppose that the grandfather of a friend of yours smoked cigarettes his entire life and never got cancer; your friend, a smoker himself, reasons that this might be because his grandfather possessed certain genes that made him more resistant to cancer, which means that your friend might have the same genes and be equally resistant to cancer. Ultimately, given that none of this is utterly impossible, your friend concludes that he can safely keep smoking. It goes without saying that smoking is a terrible idea regardless of your genetic heritage, and even though what your friend proposes is a possibility, it is by no means certain and it is not a reason to think that he is certainly going to be any safer from the negative effects of smoke than anyone else.

A much simpler example is that of people who believe that because it is possible that they will win the lottery if they keep playing, then they eventually will. As a matter of fact, most people who regularly play the lottery never win—if they did, this business would hardly be sustainable.

Occurrences in life extension

This fallacy is often observed when people discuss potential negative outcomes of defeating aging—for example, someone could think that, for a long while, therapies will probably be unaffordable for most people and, therefore, implicitly conclude that this will necessarily be the case. This fails to take into account the things that could be done to prevent this unwanted outcome from happening, such as lobbying efforts for government subsidies or the fact that paying for people’s rejuvenation may prove more economically convenient for a government in the long run.

Such preventive or mitigative actions are sometimes incorrectly dismissed using similarly incorrect arguments, such as assuming that lobbying efforts are likely to fail and thus will necessarily fail; additionally, evaluation of these probabilities often relies on supposed truisms that appeal to people’s indignation to perceived injustice, i.e. “Politicians/Big Pharma would never allow this,” not on any real, supporting evidence. (This is another instance of the appeal to anger.)

How to deal with this fallacy

Mention that whether something is possible doesn’t make it certain; additionally, likelihood must be established accurately, not through gut feelings.

Appeal to self-evident truth

Aliases: —

External sources: Logically Fallacious

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

This fallacy is committed whenever a claim is presented, without proof, to be a self-evident truth when, in fact, it isn’t. Such claims are often clichés that have been perpetuated long enough to feel like common sense though they have no or weak justification.

General examples

One example of clichés often presented as self-evident is “You can’t appreciate a good thing until you lose it”; while it may certainly happen that you fail to notice something until that something isn’t there anymore, this sentence is logically equivalent to “If you appreciate a good thing, then you must have lost it” (because if you hadn’t lost it, then by assumption you wouldn’t be able to appreciate it); however, there are no grounds to say that, in general, someone can never appreciate her own health, the love of a companion, or any other good thing while they’re still there.

Occurrences in life extension

Typical life extension-related examples are “death gives life meaning”, “we should make room for future generations”, “living forever would be boring”, and similar phrases to which many people nod approvingly without question. These are all claims that may feel vaguely or intuitively true, often because they’ve been repeated ad nauseam or because they appeal to the alleged wisdom of accepting death—which is yet another thing often presented as a self-evident truth.

It’s not at all clear why, for example, life would be meaningless without death or how this meaninglessness would manifest. Would you feel it throughout your entire life if you knew that you would never die, or perhaps your life’s past, present, and future would all of a sudden turn meaningless the moment you knew that you won’t die, ever? Alternatively, is your life meaningless by default and only acquires meaning the moment you die? These questions don’t have a clear-cut, one-size-fits-all answer (if any answer at all), so the claim that death gives life meaning is very far from being self-evidently true. To top it off, meaning is not an intrinsic property and depends on an observer, so death cannot be a necessary or sufficient condition to give everyone’s life meaning; for different people, life can be meaningful without death (for example, you may find meaning in doing something that gives you satisfaction), yet other people might find that death is necessary for their lives to have meaning but that they also need more than just that.

Boredom cannot be assumed to be a given of even an eternally long life, because it’s uncertain whether more forms of playful or intellectual entertainment will be available in the future; the concept of having to make room for future generations rests on shaky grounds, as there is no proof that the death of current generations is necessary for the sake of future ones, nor is it reasonable to ask existing people to give up on health and life for the sake of people who do not actually exist yet.

How to deal with this fallacy

Ask for evidence. What is self-evident to someone may not be to someone else, and no claim, no matter how obviously true, should be accepted on the grounds of its supposed self-evidence alone.

Appeal to worse problems

Aliases: Fallacy of relative privation

External sources: Logically Fallacious

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

An appeal to worse problems consists of claiming that a given problem is not very serious because there are other, allegedly worse, problems, ultimately in an attempt to belittle or discount the original problem. The “worse problems” presented might or might not be relevant to the original context; if they aren’t, the fallacy is even more serious.

The gravity of a problem is often hard to establish objectively; different people may have different opinions on how serious a problem is or which problem is more serious than which. Even assuming that ordering problems by seriousness in an universally accepted manner were possible, a problem may well be less serious than others and yet be extremely serious; the fact that 10 sextillion is smaller than 20 sextillion doesn’t make it a small number—just smaller than the other one.

General examples

One example is when you are told to be happy with your unfulfilling job because so many other people don’t even have jobs and are thus worse off; these people may well have a more serious problem than yours, but this doesn’t mean that being stuck in a job you dislike isn’t a problem worth consideration.

An extreme example would be scoffing at the problem of sexual harassment in the workplace because climate change, or starving children, is a worse problem. These problems aren’t even vaguely related to each other, so while one might argue that climate change has the potential to kill far more people than however many are victims of harassment, not only does this not mean that harassment isn’t a problem, it is also an example of faulty comparison.

Occurrences in life extension

Typically, the appeal to worse problems fallacy manifests in life extension discussions when someone says that there are worse problems than aging and, therefore, we should dedicate our resources to solving those instead. This claim can be countered in different ways. You can point out the fact that aging kills more people than all other causes of death combined (roughly 100,000 out of 150,000 people a day), often after decades of suffering and reduced independence, and it may thus be argued that it is the most serious problem in terms of lives lost; you can also observe that dedicating resources to defeating aging doesn’t automatically imply that other problems can’t be dealt with as well. (This is a case of false dichotomy—the fallacious assumption that only two mutually exclusive options are available when, in fact, there are more.)

How to deal with this fallacy

Sinking this fallacy is easy when you point out the following:

- Conclusively establishing which problems are worse than which is hardly feasible.

- Even if problem A is assumed to be worse than problem B, that doesn’t mean B isn’t worthy of attention.

- If problem A and B aren’t related, point it out. You don’t want the discussion to be derailed.

- Multiple problems can be tackled at the same time.

- If what you’re discussing is aging, point out how the 100,000 people killed by aging every day, and the decades of suffering that often precede their deaths, make at least a rather strong case for aging being one of the most serious problems we have.

Argument from age

Aliases: wisdom of the ancients, appeal to ancient wisdom

External sources: Logically Fallacious

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

The premise of this fallacy is that previous generations, or more vaguely “the ancients”, knew better than we do; therefore, we should do or think certain things the way they did.

General examples

The most immediate example of this fallacy is probably that of Mayan prophecies or stories from other ancient civilizations. Some people take old, intriguing-sounding nonsense about the end of the world or alien visitors as truth because, supposedly, the ancients knew things we don’t. Probably, this is because we’re generally fascinated by the idea of ancient secrets shrouded in mystery, and this fascination can weaken our logical thinking skills and push us to believe something without real proof.

A simpler example is that of products that are supposedly superior because they are “just like our grandparents used to make” and home remedies recommended by grandma. Just because our grandparents believed in a thing does not make it correct.

Occurrences in life extension

Rather than being committed by people who oppose rejuvenation, some people think that “the ancients” had the secret to longevity all figured out, and that by eating the way they did, we can live much longer lives. People who believe this can easily be taken advantage of by marketers of suspicious, alleged anti-aging supplements that haven’t passed any form of clinical testing; the usual claim is that the contents of the supplement are what some ancient civilization with great ancient-people wisdom used to eat, so you should, too.

How to deal with this fallacy

Needless to say, not only didn’t the ancients always know best, but, by and large, they were far, far more ignorant on just about everything than we are. (This is fortunate; if the ancients always knew best, this would mean that the very first generation of humans had figured everything out, and, far into the future, we would know pretty much nothing.)

If someone commits this fallacy, remind that person that people in the past used to think that you could use mercury to cure some ailments, which is a really bad idea, since mercury is extremely poisonous. This counterexample alone should suffice to show that knowledge from the past is not necessarily more accurate than present-day knowledge, especially not simply by virtue of being what ancient people believed. Every claim needs to be backed up with evidence; who believed it, or when it was believed, makes no difference.

Argument from incredulity

Aliases: argument from personal astonishment, argument from personal incredulity, appeal to common sense

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: Belief bias

Description

This fallacy can be summarized as “I can’t imagine how this could be true, therefore it isn’t.”—which is why, with a pinch of malice, I like to call it “argument from lack of imagination”.

General examples

One might find it unbelievable that the Sun is a giant ball of gas that’s been undergoing nuclear fusion for billions of years, but that’s still what’s happening; whether someone believes it or not doesn’t make it any more true or false, and nuclear fusion works the way it does even if someone can’t fathom how.

The reason why this fallacy is also known as “appeal to common sense” is that it leads to erroneous conclusions that indeed appear to be just common sense. Thousands of years ago, the idea that matter was made of air, fire, earth, and water was common sense, as these four things were commonly observed, whereas subatomic particles weren’t even imaginable; it would have seemed incredible that minuscule particles that nobody had even seen could be the constituent blocks of everything, especially when another possible explanation, based on real, observable things, was available. Yet, the conclusion that these four elements make up everything was completely wrong, and it’s definitely not common sense anymore.

Occurrences in life extension

In the context of rejuvenation, this fallacy manifests as extreme skepticism of the feasibility of defeating aging. Most people don’t know the root causes of aging or that they’ve been proven to be malleable, and most people have grown up in a world where aging is commonplace and apparently inevitable. They cannot imagine how it would be possible to interfere with aging and have thus a hard time believing that it is feasible. To them, the inevitability of aging is just “common sense”.

How to deal with this fallacy

Obviously, whether something is true or not doesn’t depend on one’s ability to understand it or to imagine how it might be possible; beyond pointing that out, assuming that you’re dealing with reasonably educated and open-minded people, the best way to counter this fallacy is to provide a good explanation of the object of their incredulity so that the very reasons why they’re incredulous may trickle away. In the case of aging, explain what it is and the progress that has been made in the laboratory.

Argument to moderation

Aliases: fallacy of the mean, argumentum ad temperantiam

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

This is the fallacy by which one infers that the middle ground between two opposing positions is necessarily always correct or the best option. Even though “in media stat virtus” (“Virtue is in the middle”) is an old Latin phrase, it’s easy to come up with examples where this doesn’t necessarily work.

General examples

An obvious example would be asserting that being healthy 50% of the time is superior to always being unhealthy or being healthy all the time. Another example would be saying that five financial losses are a good compromise between ten and no losses. Unless you really like being sick or losing money, there’s hardly any argument that can be made in favor of spending half your life sick or failing 50% of your investments. Naturally, the situation is different if, for some reason, you’re presented with a choice between, say, always being unhealthy and being unhealthy only 50% of the time. In this case, being unhealthy only 50% of the time is better than always being sick, but this doesn’t make it the better option if there’s a possibility of always being healthy instead.

Occurrences in life extension

When discussing indefinite lifespans, an example would be that living only a finite amount of time is necessarily better than not living at all or living for an infinitely long time (on the currently debatable assumption that the latter is possible). This just doesn’t work in general, because how long a life is good for you an ultimately be established only by you, and no general rule applicable to all individuals can be determined.

How to deal with this fallacy

Keep in mind that, whenever a judgment of value, such as “better”, is involved, the matter at hand is subjective and not objective; under exceptional circumstances, some people might have a reason to prefer being not fully healthy or taking a loss (though these circumstances are hard to imagine); for the very same reason, no one can infer that a middle ground will always be better than either extreme for everyone.

Double standard

Aliases: —

External sources: Logically Fallacious

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

A double standard is the act of applying different criteria to judge two situations that are, in fact, of the same kind, implicitly or explicitly suggesting a difference that just isn’t there, often with no or unconvincing arguments to back it up.

General examples

Examples of double standards are plentiful in the context of gender equality. In some social groups, it is perfectly fine if women comment on the looks of men other than their own partners, while men commenting on the attractiveness of another woman often means asking for trouble; on the other hand, I’ve met people who would react to a man cheating on his wife with “Oh, well, he’s a man—that’s understandable”, while they’d be breathing fire at the thought of a woman cheating on her own partner. In both cases, we have an action that is considered to be despicable not in its own right but rather depending on who commits it.

Occurrences in life extension

While it is generally agreed that saving lives is important (our entire medical, safety, and moral systems revolve around this principle), people who object to life extension and rejuvenation sometimes implicitly adopt a double standard when they claim that saving a young life from disease is one thing but saving the life of an older person by means of life extension is “different” when, in both cases, we are talking about employing medicine to fix a health problem that would otherwise be fatal. Another example is drawing an arbitrary line between aging and age-related diseases—suggesting that there is such a thing as “healthy” or “normal” aging as opposed to pathological aging—when the evidence says that there is no biologically meaningful distinction between the two, although, in this case, the fallacy might be committed unintentionally out of ignorance rather than lack of critical thinking or intentional deceit.

How to deal with this fallacy

If someone is guilty of a double standard, remind her that any exception to a general principle must be thoroughly justified; if she thinks that there is a difference between saving young lives and old lives, for example, ask her to explain in detail what the difference is and how it justifies a different treatment.

Fallacy of composition

Aliases: faulty induction, exception fallacy

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

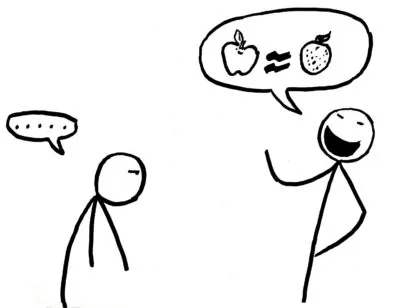

The fallacy of composition consists of generalizing to the whole a property that is possessed by a part of the whole. This is the opposite of the fallacy of division, which consists of assuming that what is true of the whole must automatically be true for parts of the whole as well. It’s easy to confuse these two fallacies.

General examples

A good example of this would be concluding that, since subatomic particles are very tiny compared to a human, then anything made of subatomic particles must also be tiny; of course, everything in the visible universe is made of these particles, including humongous stars. An example from the culinary world that happens more often than you think is the following reasoning: you like ingredient A and ingredient B; therefore, you’ll necessarily like them combined together as well. Right—fancy a watermelon-mayonnaise-coffee shake?

Occurrences in life extension

This fallacy is often committed in the context of life extension when talking about things that may be true of individual life experiences and generalizing them to entire lives, typically in an attempt to prove that living for a very long time will be boring. Life consists of a myriad of activities that, if protracted for a long time, may get boring; therefore, the reasoning goes, life would get boring too if it went on for too long.

This isn’t a sound conclusion, though, because many activities periodically regain their appeal; for example, I might be tired of playing chess for today, but I may want to play another game tomorrow; I might be tired of having worked at a certain job for the last ten years, but I might want to do it again twenty years from now. It’s also unclear whether the number of different activities that someone may enjoy is finite or not.

How to deal with this fallacy

The best way to show someone why the reasoning behind the fallacy of composition doesn’t work is probably to provide counterexamples. This will make clear that you can’t always infer that properties of parts of the whole are inherited by the whole; be careful, though, that at this point, the reply might be that you’re discussing a different case, and depending on the circumstances, this person might be committing a second fallacy, namely a double standard, to justify the previous one.

False attribution

Aliases: —

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

This fallacy consists of backing up claims with a weak or unverifiable source.

General examples

Examples of false attribution are basically examples of hearsay—think of all the times that somebody insisted that a certain home remedy is granted to work because some friend of his, who’s allegedly an expert, said so. Another example is your wacky conspiracy theorist friend who says that reptilians secretly ruling the world is a fact because that’s what it reads on a super-authoritative website whose address he can’t remember right now—and once he does remember, it turns out to be something like omgaliensarerealforrealnojoke.com.

Occurrences in life extension

The false attribution fallacy is one that people who are into anti-aging supplements should pay attention to. Supplements may be marketed as “verified by scientists”, or advertised as the number one choice of a famous but unqualified person, as a means of validation—all of which is hearsay dressed up in nicer clothes. The popularity of the celebrities who take a given supplement proves nothing in terms of its efficacy. Similarly, simply claiming that something’s got the seal of approval of “science” isn’t enough; an adequate number of references to reliable studies assessing the supplement’s efficacy must be provided. No matter how flashy, catchy, or professional-looking the ad of a drug or supplement can be, solid evidence is all that counts.

How to deal with this fallacy

You deal with this fallacy in the same way you do with many others: ask for evidence. If anyone claims to possess evidence to back up a claim, this evidence needs to be accessible, credible, and verifiable. Just saying that something is true because, ten years ago, you read it in some unspecified book (that now can’t be tracked down in any way) simply doesn’t cut it.

False dilemma

Aliases: false dichotomy, either-or fallacy, black-and-white thinking

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

A false dilemma happens whenever two mutually exclusive options are presented as the only ones, even though others are possible.

General examples

Examples typically involve ideologies or philosophical positions, such as adherence to a religion, feminism, or a political party: either you believe in God or you are evil; either you’re a feminist or you are in favor of oppressing women; either you side with political party P or you’re against freedom. In essence, the false dilemma fallacy reduces a panoply of possible positions down to two extremes.

Occurrences in life extension

When undesirable outcomes are presented as inescapable side effects of defeating aging or researching life extension, your false-dilemma alarm should go off. A typical example is the implicit assumption that is made by people who think that we should focus our efforts on problems that are supposedly worse than aging: either we dedicate ourselves to solving aging or to other problems. However, just as nothing prevents us from working on starving children and climate change at the same time, we can work on aging and the rest of the global issues simultaneously.

Another example is the following reasoning: “Either we don’t defeat aging and stave off cultural stagnation, or we do defeat aging and put up with cultural stagnation.” It is a false dilemma that these are the only options and that there will be no middle ground where aging is defeated but cultural stagnation—assuming that it would even be a consequence—is either prevented or mitigated. For example, assuming that the presence of very long-lived individuals necessarily leads to stagnation (which is uncertain at this stage and might well not happen if brain plasticity is sufficiently preserved by comprehensive rejuvenation), there is still the option of mitigating this problem through social programs that provide continuous learning.

How to deal with this fallacy

Generally speaking, this fallacy is countered by providing examples of options between the two extremes, such as an atheist dedicating his life to helping people in need.

Faulty comparison

Aliases: bad comparison, inconsistent comparison

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

A faulty comparison is drawn either between two things that aren’t really related or between certain properties of two things that are such that no meaningful information can be deduced. The goal of a faulty comparison is generally that of making something appear better (or worse) than it is.

A weak analogy and a faulty comparison might appear similar at first. However, the important difference is that the former suggests that two things are more similar to each other than they actually are; the latter doesn’t suggest any similarity between the terms of comparison but rather that one is better than the other based on some of their properties, even though there are reasons why the comparison is meaningless.

General examples

Faulty comparisons can easily be stupid comparisons—for example, if someone argued that the fastest runner on Earth isn’t that fast after all, given that an airliner is so much faster. Of course, the airliner is faster, but it’s a little unfair to compare a tireless machine to the legs of a human being; they’re built for different purposes and aren’t much related at all.

A more subtle example comes from the relevant Wikipedia article—product X is cheaper than product A, is higher-quality than B, and has more features than C; so, it must be really good, right? Wrong. Product A could be the most expensive product of that kind on the market, in which case the fact X is cheaper than the most expensive product around is rather obvious and doesn’t really tell much. Similarly, B could be the worst product ever designed, in which case being better than B wouldn’t be that hard, and C could be a basic model with the least features of all. While true, this kind of comparison doesn’t prove that X is generally better than A, B, and C or is even a good product in general, even though the faulty comparisons make this belief tempting.

Occurrences in life extension

One may easily bump into a tricky example of this fallacy when pointing out that 100,000 people die of aging every day. That might not be the best opener, as the comeback could very well be “Thank goodness! People used to die of infections!”

In this example, the comparison isn’t apparent, but we’re still dealing with one, namely between death by aging and death from infections (or whatever other cause) at a younger age, which used to be the norm. Dying of age-related diseases at age 80 is arguably better than dying of tuberculosis at age 40, and up to this point, there’s no fallacy being committed; however, it’s easy to make a leap from here and present aging as a good thing because death by aging represents an improvement over dying young to an infection—of course, it’s better, but that’d be no different than someone a hundred years ago answering “Thank goodness! People used to be eaten by wild beasts!” to anyone pointing out how infections killed millions of people before age 50. Dying of age-related diseases later in life may be better than dying of whatever else earlier on if nothing else because you get to live longer, but that doesn’t make it good.

How to deal with this fallacy

If you suspect that someone has committed a faulty comparison, you should point out why the terms of the comparison are either not related or why the comparison is not meaningful. Examples such as the ones included in this section may be helpful in driving your point home.

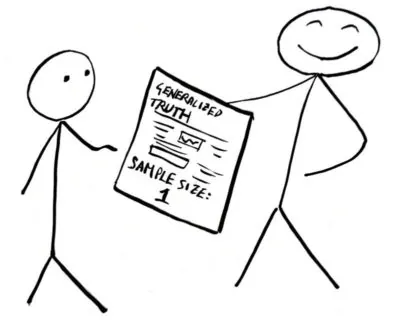

Hasty generalization

Aliases: overgeneralization, unrepresentative sample, lonely fact fallacy

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

This fallacy is committed when a conclusion is drawn based on an insufficient sample size, making an undue generalization when not enough data is available to justify doing so.

General examples

Concluding that the people of my city are poor because I bumped into ten beggars on my way to the shopping mall is an example—ten beggars don’t constitute a statistically valid sample, and much more data would be needed to draw such a conclusion. (You might be interested to know that, in fact, extreme poverty has been going down for the past 30 years.)

Occurrences in life extension

This is a fallacy that people commit when assuming that, since some pharmaceutical companies only care about profit or some politicians only care about their own interests, all pharmaceutical companies only care about profit and all politicians only care about their own interests—as you can imagine, the leap from here to “hence, rejuvenation is a bad idea” is very short for predictable reasons.

Another example is someone who claims that rejuvenation would lead to cultural stagnation because all the old people she personally knows are a bunch of stubborn, reactionary fossils who dream all day long of the good, old days when phones didn’t exist yet. Clearly, she needs better friends, but do the old people she knows represent the population enough for her to conclude that all, or at least most, old people turn out to be like that? Does it depend only on age, or does the cultural context people grow in, and the education they receive, matter at all? Will rejuvenation biotechnologies allow older people to retain youthful brain plasticity? These questions need answers before we can generalize your friend’s observation to the average behavior of older people in a world with rejuvenation.

How to deal with this fallacy

The best way to counter this fallacy is to always remind people (and yourself!) that sample size matters. Try telling them the following joke.

A statistician, a physicist, and a mathematician sit on a train in Scotland. Suddenly, they see a black sheep from the window. The statistician says, “In Scotland, all sheep are black.” The physicist corrects him: “No; in Scotland, at least one sheep is black.” The mathematician shakes his head in frustration and says, “Not at all. In Scotland, at least one sheep is black on at least one side!“

The goal of the joke is clearly to poke fun at a mathematician’s pedantry (if a sheep is black on one side, it’s safe to assume that it’s black on the other side too), but it also serves to highlight the importance of sample size. A good statistician would hardly claim that all sheep in Scotland are black just because the size-one sample he observed was black; a sample that small means nothing more than what the physicist said: there’s a black sheep in Scotland.

Inflation of conflict

Aliases: —

External sources: Logically Fallacious

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

This fallacy is committed when someone infers that, if experts cannot agree on an issue, then there is no conclusion to be reached; the people who commit this fallacy often leap further and infer that the experts don’t know what they’re talking about, so some other conclusion (generally one that suits the author of the fallacy) can be assumed to be true instead—or, worse, the validity of the entire field can be called into question.

General examples

An example of this fallacy involves reasoning that is sometimes heard in response to contradicting nutrition studies. Nutrition science is anything but clear-cut, and these kinds of studies often contradict each other. For example, a dispute on whether a high-fat diet causes high blood cholesterol may lead some people to conclude that, since scientists can’t make up their minds about it, stuffing one’s face in French fries on a daily basis is perfectly fine—it’s not, for a variety of reasons that go beyond your cholesterol, and scientists’ disagreement on whether A or B is true doesn’t make C true.

Occurrences in life extension

At this stage of the development of life extension science, disagreement is pretty much an item on the agenda; different experts disagree on approaches, implementation details, causes and effects, timelines, and, somewhat rarely, even on feasibility. Unlike what some people may think, this doesn’t mean that life extension is poppycock that can be safely disregarded; it only means that, at what is pretty much this science’s infancy, many things are unknown and scientists may have conflicting views. More research is bound to resolve these conflicts.

How to deal with this fallacy

More than from opponents of rejuvenation, you can expect this fallacy from frustrated sympathizers who would like to see more progress but are upset when they see that experts disagree, as that may make them feel as if the goal were getting further and further away. Whether you’re talking rejuvenation or something else, point out that even total disagreement on an issue doesn’t mean that the issue can be disregarded or that opinions other than the proposed ones are necessarily correct—it only means that we haven’t fully understood the issue yet; the issue, whatever it may be, doesn’t need our understanding it to be the way it is.

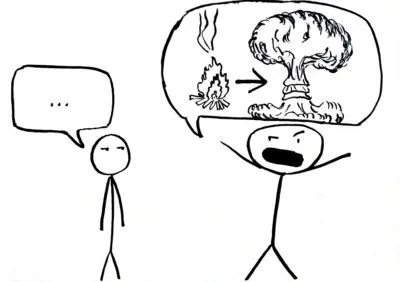

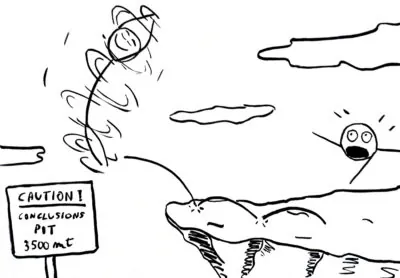

Jumping to conclusions

Aliases: hasty conclusion, leaping to conclusions

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

This fallacy is as common as it is straightforward: it consists of drawing a conclusion hastily, without taking sufficient time to analyze data or evidence, and is often only based on prejudice or gut instinct.

General examples

An example of this fallacy is concluding that smoking is not bad for you because you know somebody who has been smoking for 30 years and yet is alive and well. Biology is ridiculously complicated, and the reasons why somebody might get away with smoking for such a long time without (apparent) consequences are equally complex and need to be taken into account; you can’t just say that if your acquaintance is still alive after 30 years of smoking, then it necessarily means that smoking is not bad for you. (If you did that, it wouldn’t just be a case of jumping to conclusions but also one of hasty generalization.)

A simpler example would be concluding that, since Bob is standing next to a broken window holding a hammer, then he must necessarily be the one who broke the window. While the circumstances make him a suspect, a more attentive examination of the situation might reveal that, for example, there is a heavy rock lying on the floor by the window frame, surrounded by glass shards, and that Bob is holding a hammer because he wanted to fix a chair. (Further investigation might reveal that the rock was thrown at your window by your neighbor because he does not like people who jump to conclusions.)

Occurrences in life extension

In the context of life extension, jumping to a conclusion is probably the most common fallacy. People who are first introduced to the topic are particularly quick to conclude that life extension would inescapably lead to overpopulation, eternal boredom, immortal dictators, and all kinds of catastrophes without stopping to consider any evidence of the contrary first or even if the risk of any of these problems would be worth the benefits of defeating aging. This is pretty much a textbook case of blindly following one’s gut instinct.

However, rejuvenation advocates too must be on their guard; they can easily fall prey to this fallacy as well. A classic example is the assumption that rejuvenation biotechnology will necessarily be cheap because all technology eventually winds up being cheap. The assumption is questionable per se—particle accelerators haven’t become very affordable over the past 50 years—but even conceding that a lot of technology that consumers would care about does eventually get cheap enough, this is still insufficient to claim certainty. Provided that sufficient relevant data—i.e., prices of other biotechnology products or drugs rather than smartphones—are available to show that most technology becomes cheap enough for consumers to buy, this would only allow us to infer that rejuvenation biotechnology is likely, not certain, to become affordable within whatever timeframe; no one is clairvoyant.

How to deal with this fallacy

If you are discussing with someone who jumps to conclusions, you will need to take the time to present evidence that questions the validity of those conclusions, so be sure to have it ready; counterexamples to the hasty conclusions may also help, especially if you’re talking life extension. A skeptical opposer is extremely likely to resort to other fallacies, such as “everybody knows that…” arguments—other people in the discussion may easily buy into such a flawed argument and will expect you to provide evidence rather than the other person.

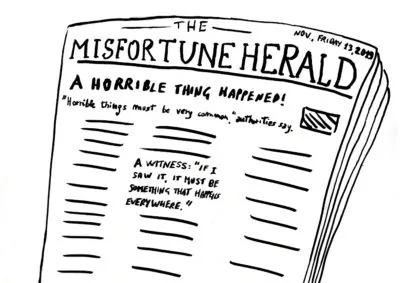

Misleading vividness

Aliases: —

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: Availability heuristic

Description

Misleading vividness is the fallacy committed when you let a small sample of emotionally charged events convince you that these events are generally likely to happen. This more often occurs with events associated with negative feelings—a single suicide attack is more likely to make you fear that several others might take place soon than winning the lottery is likely to make you think that winning money is a common thing. Naturally, the likelihood of any event bears no correlation to the emotions that we may associate with it.

General examples

Have you ever noticed a beggar on the street and thought that poverty is on the rise? Have you ever heard that your neighbor was robbed and concluded that your neighborhood is not safe anymore? More generally, have you ever heard bad news on the TV and concluded that the world is getting worse by the minute? If you answered yes to at least one of these questions, then you experience a perfectly normal emotional reaction to negative happenings; however, if you stuck to your conclusions even after the wave of pessimism that the bad news cast on you, then you are also guilty of misleading vividness. None of the premises in the three examples above justify the conclusions, though is easy to come to them when you are overwhelmed by negative emotions.

Occurrences in life extension

This fallacy lies at pretty much the core of the dystopian future objection—the idea that the world is headed for disaster and thus life extension is not worth considering. While the world is far from being an ideal one (assuming an ideal world can be uniquely defined), but relatively few dramatic events or situations, such as civil wars or poverty, do not constitute evidence that the world is going downhill—as a matter of fact, evidence points to the contrary.

How to deal with this fallacy

To counter this fallacy, it is advisable to provide data showing how things are better than what a small sample of negative events might suggest, as well as point out how the vividness of a negative event may make one neglect contrary statistical evidence. It is not advisable to engage in such a discussion with people who are currently overwhelmed by negative emotions—understandably, they won’t listen, and you are likely to make them even more entrenched in their views.

Naturalistic fallacy

Aliases: is–ought fallacy

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

The naturalistic fallacy, which is not the same as the appeal to nature fallacy, is committed whenever one assumes that the way things are is the way they ought to be. This fallacy betrays the belief that nature, or some kind of superior entity anyway, has set everything up for the best, even when we fail to see why a certain thing is good even though it appears to be bad. Needless to say, none of this is particularly likely.

General examples

A luckily outdated example of the naturalistic fallacy is that of infant mortality. Back when most children never reached adulthood, a person could have erroneously concluded that since high infant mortality existed, it ought to have existed; today, you wouldn’t make many friends by holding this belief.

Another example consists of concluding that, if somebody is born with a disability, then that’s the way things should be—someone might push the “reasoning” even further and conclude that if a way existed to correct this disability, it should not be employed.

Occurrences in life extension

In the context of life extension, this fallacy is observed when people say that, given that people age biologically (and they always have), then they ought to, so rejuvenation shouldn’t be pursued. A similar example is saying that since people die sooner or later, then they ought to, irrespective of their desires on the matter.

How to deal with this fallacy

In theory, one way of dealing with this fallacy would be to punch the person in the face and say that’s what ought to have happened because it did happen—but I don’t recommend this approach. Rather, remind the person that whether something ought to be can only be decided by an observer; there are no absolute oughts. This means that there may be different answers, depending on who you ask, and a good principle to stick to is that you should not impose your will on others—if nothing else, because otherwise they might feel justified in doing the same to you, which is nothing but the prelude to war. So, if people think that aging ought to be, for example, they should be free to stick to their belief and age to death, but they should not be allowed to force others to endure the same fate; in other words, aging shouldn’t ought to be for people who don’t want it.

A quicker way to counter this fallacy is to bring up examples of things that exist but, in most people’s views, ought not to, such as murders, rapes, and wars.

Nirvana fallacy

Aliases: perfectionist fallacy

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

The Nirvana fallacy can be summarised as “if it’s not perfect, it’s not good enough”; either you reach Nirvana right away, or any attempt is a total waste of time. Intermediate steps and cumulative progress do not matter; either perfection is reached in a single step, or the proposed solution is not good enough.

General examples

An example of this fallacy is thinking that bulletproof vests are not a good solution to protect police officers’ lives, because the real solution would be that people learned not to shoot other people in the first place. (In a world like that, police officers would hardly be needed anyway.) Surely it would be fantastic if criminals and police officers had a gentlemen’s agreement preventing them from shooting each other, but that is hardly going to happen; bulletproof vests are not useless or an insufficient solution just because it would be better if police officers were never shot in the first place—any police officer whose life was saved by a bulletproof vest can confirm this.

The example above is an abstract one; a far worse one, which unfortunately comes from a real-life conversation, is that of an antirape device, invented by an African woman as a means to help local women protect themselves from rapists, which was discounted by a friend of mine (a woman, to top it all) as not a “real” solution, because the real one would be that, verbatim, “men learned not to rape”. Forgetting for a moment that the author of this claim was also guilty of hasty generalization (as she was implicitly suggesting that all men are rapists), it is immediate to see that a world where no one ever rapes anyone, while highly desirable, is unfortunately also rather unrealistic, at least for the time being; any solution that can help reduce the number of rapes is very much welcome, even if it doesn’t eradicate the problem altogether.

Occurrences in life extension

This fallacy is usually committed when discussing the dystopian future objection to rejuvenation; in this kind of discussion, advocates generally end up providing evidence that the world is better than most people think, although not perfect; it is this lack of perfection that triggers some people to object that, even though poverty is gradually disappearing, the world is more peaceful than ever, and democracies are on the rise, there still are poor people, conflicts, and dictatorships; this, they say, suggests that the world isn’t perfect and so you shouldn’t bother them with talking about rejuvenation before the world does become perfect—whatever that means.

The Nirvana fallacy is also committed by people who think that rejuvenation is useless because death is allegedly inevitable. Death is currently inevitable because aging will kill you if nothing else does it first; if aging is taken out of the equation, so is this certainty—even though this does not mean that you are granted to live forever. Even neglecting this fact, and assuming that you would certainly die at some point of whatever cause, rejuvenation would prevent you from ever suffering from age-related diseases and would allow you to enjoy life for longer, which is definitely an improvement. Besides, if the supposed inevitability of death makes life extension pointless, one could argue that living at all is pointless—unless there is some reason why the heat death of the universe makes a life of 120 years worthless but not one of 80. Thankfully, not too many people jump off a cliff just because they think death is inevitable anyway.

How to deal with this fallacy

If you are faced with someone committing this fallacy, try reminding them that hardly anything, and especially grandiose achievements, is ever fully accomplished in a single step—Rome wasn’t built in a day, and any improvement is a good thing, even if it doesn’t lead to perfection. In addition to that, whether a solution is good enough depends on your goal—if your goal is to completely eliminate policemen murder, then bullet-proof vests won’t cut it; if your goal is to decrease the number of policemen murdered, then they definitely are good enough, even though this doesn’t mean that better, more effective solutions shouldn’t be searched for.

Oversimplified cause

Aliases: fallacy of the single cause

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

This fallacy consists of attributing a single cause to a given phenomenon that actually has a more complex etiology. Put differently, this fallacy consists of assuming that, if A is a contributing factor to B, then A is a sufficient condition for B to happen.

General examples

Since we know that smoking can cause cancer, you might be tempted to think that, if you ban smoking, you can prevent cancer; however, this is not true, unfortunately. Smoking certainly is a contributing factor to cancer, but it is neither necessary nor sufficient for cancer to develop. Some people smoke their entire lives and yet never get cancer; others never touch a cigarette, yet they develop cancer anyway. Banning smoking can certainly prevent some cases of cancer, but it will not eradicate any form of cancer.

Occurrences in life extension

Sometimes, people say that aging has good sides too, such as growing life experience. Setting aside the erroneous conflation between chronological and biological aging committed here, the underlying, oversimplifying assumption is that (chronological) aging is a sufficient condition to accrue life experience, which is just not true. If you are 200 years old, but you spent those years in your tiny, godforsaken town, always doing the same job, not studying much, never seeing many people, and steering clear of any learning opportunity, your 200-year-long experience will hardly be comparable to that of a 30-year-old who has spent the last 20 years of his life traveling around, studying a lot, meeting people, and taking every opportunity to learn more about the world around himself. Clearly, chronological aging is a necessary condition for experience to be gained—if chronological aging didn’t happen, that would mean that time wasn’t passing and nothing at all could happen—but it’s not a sufficient condition to gain more experience.

Questionable cause

Aliases: confusing correlation and causation (or cause and effect), causal fallacy

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

This is actually a class of several slight variations of the same fallacy, the core error being failing to tell correlation from causation—that is, incorrectly identifying the cause of a phenomenon by relying only on correlation.

General examples

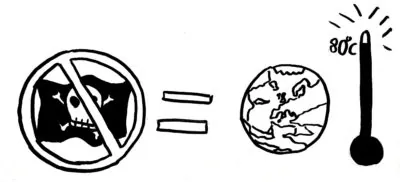

A hilarious example is that of pirates and global warming by the Church of The Flying Spaghetti Monster. Over the past three centuries, the number of pirates has been going down, and at the same time, global temperatures have been going up; these two phenomena are correlated (i.e., they happen to be observed at the same time), but unless you were several French fries short of a happy meal, you would never think that the decline in the number of pirates is causing global warming—which is exactly what the CFSM suggests to mock this kind of fallacious reasoning.

Occurrences in life extension

This fallacy often blurs with the oversimplified cause fallacy when discussing the connection between aging and experience. Since the insults of aging, whether they are merely cosmetic or serious diseases, often do correlate with wisdom and life experience, some people claim that aging is what brings wisdom and experience; undo aging, and you undo that experience. The questionable cause fallacy is revealed with the understanding that biological aging and wisdom and experience are not linked by a causal relationship but are merely correlated; they both require the same necessary condition to happen (chronological aging, i.e. the passing of time), but this requirement isn’t the only one. Biological aging requires the accumulation of several types of damage (since that’s what it is), whereas life experience and wisdom require many factors to happen—including, but not limited to, chance, determination, and curiosity.

How to deal with this fallacy

“Correlation does not imply causation” is a mantra of science, and for good reason—you could plot all sorts of correlated variables and get a neat line with a clear trend, but that does not mean that there is any causal link between the two. This is what you should point out to anyone who commits this fallacy. For example, people who are biologically (and chronologically) older normally have taken a higher number of total steps in their lives than people who are chronologically and biologically younger; does this mean that walking makes you older or that getting older makes you walk more? Exactly.

Reification

Aliases: concretism, fallacy of misplaced concreteness

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description

The fallacy of reification consists of treating an abstraction as if it were a concrete object or person. Reification is often used in language in a poetic or rhetorical way—in which case, it is not a fallacy, as it is not intended to prove anything but just to convey an idea in a more beautiful or understandable fashion—but it is a really bad fallacy when you actually use it to back up an argument; yet, a lot of people often buy into it because it generally relies on widespread figures of speech.

General examples

You probably have heard plenty of people saying that life was mean to them; more often than not, this is just a way to say that they have to put up with a lot of difficult things throughout their lives, but if repeated long enough, some people might actually convince themselves that life has got a will of its own and intends to harm them, and they use this as an excuse to avoid attempting to make their own lives better.

Another example of reification is when chronically sick or disabled people personify their ailments, attributing them intentions and, in some cases, even seeing their ailments as some kind of life companions that they would miss if these ailments were to go away. Even death is personified as “the great equalizer”—some kind of entity that is there for the sake of making everyone equal at least in one aspect. It goes without saying that death is nothing of the sort, but if it were, it would be worth pointing out that no one actually ever explicitly asked it to do any such thing.

Occurrences in life extension

The best example of this fallacy comes straight from the typical objection to life extension, or, more generally, to any new technology radical enough to push the conservative buttons of some people, who reply that “Nature knows best.” Nature does not know anything. Nature isn’t an entity with a brain that can store, retrieve, or use information. “Nature” is an abstraction, a collective noun to indicate basically anything that is not human made or that happens entirely without human intervention; it’s not an entity who sat down and planned the universe from scratch or knows better than people what should or should not be done for the sake of an imaginary, poorly defined greater good. Nature doesn’t know what’s best for anyone or anything and doesn’t care about humans, or anything else—not out of ill intentions, but simply because it can’t. Life is not an episode of The Smurfs.

How to deal with this fallacy

Most people aren’t crazy—they don’t really think that Mother Nature exists as such or that death has a hobby of making everyone equal, but the problem is that this fallacy relies on ambiguity; even though people can tell that Mother Nature is not a real person, they still often somehow believe in its ability to do things for the best, mostly because this kind of rhetoric has been repeated over and over for centuries, and, as often happens with lies, if you repeat them long enough, they will become truths in people’s minds. You need to break through this ambiguity by explaining how the erroneously personified concept does not possess any of the qualities of a person and cannot act as such, for good or bad; it might appear to be otherwise, but that is only an appearance fueled by our spontaneous tendency to personify things that are not human. As you make your point, try not to be patronizing—in this case, it can be very easy to unintentionally do that.

Selective attention

Aliases: —

External sources: Logically Fallacious

Related cognitive biases: Belief bias

Description

“Selective attention” is a way of saying that you are seeing only what you want to see. It can manifest as a kind of cognitive bias—that is, you unintentionally see only certain aspects of a situation either because you are positively biased towards them or negatively biased towards those which you are not seeing—or it can be an intentional deception. Selective attention often leads to a hasty generalization—first you see only what you want to see, and from that, you come to an undue, generalized conclusion that simply does not hold water.

General examples

Typical examples involve global issues, such as the economy, poverty, and world hunger, that are hastily judged to be worse than they actually are. For example, you might notice many beggars on the streets of your city and conclude that poverty is on the rise; however, global data on poverty shows that it has been declining for decades. Focusing exclusively on the beggars on the streets has led you to the wrong conclusion.

Another example is that of smartphones. Smartphones can be really distracting, indirectly force you into a bad posture, and make you spend far too much time on your Facebook feed. If you focused only on these things, you could conclude that smartphones are the worst idea ever, but that neglects the fact that they allow for instantaneous communication with virtually anyone in the world at near zero cost, and they let you check your email and your bank account, pay your bills, keep an eye on your pet at home, buy your transportation ticket, check in well before you even get to the airport and skip the queue, take a picture of something and quickly identify it, and so on.

Occurrences in life extension

In the context of aging, selective attention often manifests as a tendency to notice potential downsides of life extension, such as boredom or overpopulation, while disregarding not only the benefits that would derive from bringing aging under medical control but also how big a problem aging actually is on the personal, social, and economic levels. The idea that life extension is not a good thing because the future might not be worth living in is also a product of selective attention—focusing on negative information about world trends while disregarding positive information that shows how the world has been slowly but steadily improving for centuries on virtually all fronts.

How to deal with this fallacy

If somebody only sees what he wants to see, the best medicine is to point out to him what he does not want to see. Especially when people want to prove something that they dislike is bad, such as life extension, they will tend to see only downsides, especially if these are relative to very polarised or emotionally charged issues. Do not deny potential downsides if they actually exist, but do point out the upsides that are being neglected.

Shifting the burden of proof

Aliases: onus probandi

External sources: Logically Fallacious, Wikipedia

Related cognitive biases: —

Description