A recent study analyzed data from over 15,000 participants and their intake of 11 vitamins, and the results suggested that higher vitamin intake, particularly of Vitamins C and B2, is associated with slower biological aging [1].

Beneficial molecules

One of the easiest and most accessible ways to improve health and lifespan is to consume a diet and supplements that provide adequate nutrition. Studies conducted in cell cultures and animals suggest that various vitamins, through their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, have beneficial effects against aging processes [2, 3]. Human data suggest that vitamins have specific benefits, including improved lipid levels, better cognition and memory, reduced incidence of age-related macular degeneration, and lower mortality in cancer patients [4, 5, 6].

More granular approach

We recently covered a review that discussed the impact of multivitamins and minerals on health and longevity. That study analyzed the findings from 19 meta-analyses published in the last 25 years. While that study took a broad look at the impact of vitamins and minerals on different aspects of health, this study took a more granular approach and investigated the impact of 11 vitamins (A, B1, B2, B3, B6, B9, B12, C, D, E, and K), from both dietary and supplementary sources, on different aspects of biological aging. The authors used data from 15,050 participants, with a median age of 51 years, who were part of the nationally representative National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2007 and 2018.

The authors used three methods to measure different aspects of biological aging: the Klemera-Doubal method biological age (KDM-BA), PhenoAge, and homeostatic dysregulation (HD), each using multiple different biomarkers to assess the speed of biological aging.

The choice of these aggregated measures of biological aging stems from limitations in previous studies, which often focus on single aging-related outcomes, whereas aging is a process that affects multiple systems. Therefore, measuring the speed of aging using aggregate measures of aging that incorporate multiple biomarkers is an attempt to reflect the complexity of the process.

All together and one-by-one

The epidemiological data on the relationship between vitamin intake and biological aging have limitations; for example, studies often focus on the impact of a single vitamin rather than a vitamin complex, which more accurately reflects reality. Those who investigate vitamins in combination often do not examine the effects of individual ingredients within the mixture. To address this gap, those researchers analyzed both scenarios.

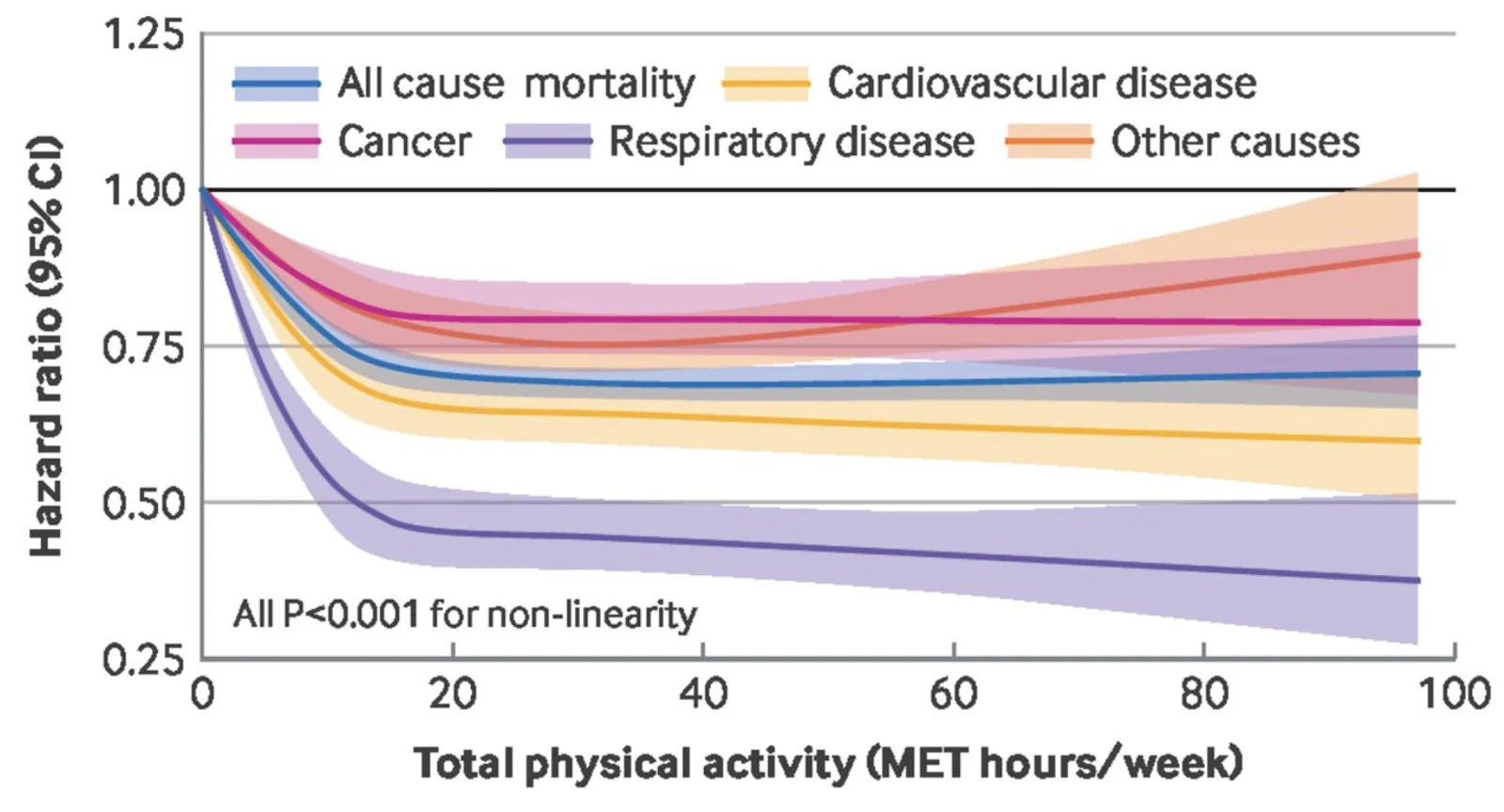

An initial analysis, which divided participants into four quartiles by total vitamin intake, showed that those in the highest quartile were, on average, older, had higher socioeconomic status, and had healthier lifestyles. All three metrics of biological aging showed less accelerated aging in the highest quartile group than in those in the lowest quartile. After adjusting for multiple factors, the highest quartile still showed lower biological age acceleration, as measured by KDM-BA and PhenoAge; however, while there was a trend toward reduced age acceleration, the association was not statistically significant for HD.

The researchers also examined the effects of individual vitamins. Reduced biological aging was observed among individuals in the highest quartile for all vitamins, as measured by PhenoAge, but only for B2, B9, and C Vitamin intake, when measured by KDM. In contrast, analysis of HD didn’t show a significant impact of any vitamin.

Biological aging indicators agreed that among all vitamins tested, Vitamin C was the “primary protective driver.” B2, important for supporting metabolic and immune health, came in second. The researchers suggest that the potent role of Vitamin C might stem from its antioxidant effects, which protect against aging-related oxidative damage.

On the other hand, the results suggest that Vitamins B12 and D may have adverse effects. Vitamin B12 is important for blood and nerve cells health and helps make DNA. Vitamin D has many bodily functions, including calcium absorption in the gut; metabolism of calcium, phosphorus, and glucose; bone growth support, remodeling, and mineralization; reduction of inflammation; modulation of cell growth; and neuromuscular and immune function. The researchers suggest the adverse effects of Vitamin D may be due to the absence of a linear, dose-dependent relationship between Vitamin D intake and biological aging, in which higher doses accelerate aging, but this remains to be tested.

We have previously reported on the complex relationship between Vitamin D and the biology of aging. For example, while studies have linked Vitamin D supplementation to slower epigenetic aging, other research suggests that in some cases Vitamin D supplementation may not be beneficial, as a study published in Aging Cell suggests that administering Vitamin D to Alzheimer’s patients may actually make the problem worse.

Subgroup differences

The effects of vitamin intake were found to vary based on demographic and health characteristics. Males, people with a BMI under 30, current alcohol drinkers, people with lower education levels, people who ate less than 1500 calories a day, and people with comorbidities saw more beneficial effects. These results suggest that “individuals with higher underlying physiological stress or inflammation might derive greater benefit from adequate vitamin intake.”

When an analysis was conducted using only dietary data, the researchers obtained similar results: a protective effect of total dietary vitamin intake and a prominent role of Vitamin C in joint protective effects, highlighting the importance of obtaining vitamins through a healthy, whole-food diet.

Achieving nutritionally adequate levels

This study contributes to the growing body of evidence linking vitamin-rich diets to reduced biological aging. [7,8]. However, supplementation doesn’t have to imply taking excessive amounts, as the authors highlight that the “higher intake in our study primarily corresponds to achieving nutritionally adequate levels: over 90% of participants in the highest intake quartile met the Recommended Dietary Allowance for most vitamins.”

We would like to ask you a small favor. We are a non-profit foundation, and unlike some other organizations, we have no shareholders and no products to sell you. All our news and educational content is free for everyone to read, but it does mean that we rely on the help of people like you. Every contribution, no matter if it’s big or small, supports independent journalism and sustains our future.

Literature

[1] Zhang, X., Xu, Y., Wang, X., Chen, M., Xiong, J., & Cheng, G. (2026). Association between vitamin intake and biological aging: evidence from NHANES 2007-2018. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 30(2), 100776. Advance online publication.

[2] Monacelli, F., Acquarone, E., Giannotti, C., Borghi, R., & Nencioni, A. (2017). Vitamin C, Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients, 9(7), 670.

[3] Kaźmierczak-Barańska, J., & Karwowski, B. T. (2024). The Protective Role of Vitamin K in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Nutrients, 16(24), 4341.

[4] Seddon J. M. (2007). Multivitamin-multimineral supplements and eye disease: age-related macular degeneration and cataract. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 85(1), 304S–307S.

[5] Yeung, L. K., Alschuler, D. M., Wall, M., Luttmann-Gibson, H., Copeland, T., Hale, C., Sloan, R. P., Sesso, H. D., Manson, J. E., & Brickman, A. M. (2023). Multivitamin Supplementation Improves Memory in Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 118(1), 273–282.

[6] Harris, E., Macpherson, H., & Pipingas, A. (2015). Improved blood biomarkers but no cognitive effects from 16 weeks of multivitamin supplementation in healthy older adults. Nutrients, 7(5), 3796–3812.

[7] Canudas, S., Becerra-Tomás, N., Hernández-Alonso, P., Galié, S., Leung, C., Crous-Bou, M., De Vivo, I., Gao, Y., Gu, Y., Meinilä, J., Milte, C., García-Calzón, S., Marti, A., Boccardi, V., Ventura-Marra, M., & Salas-Salvadó, J. (2020). Mediterranean Diet and Telomere Length: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 11(6), 1544–1554.

[8] Hu F. B. (2024). Diet strategies for promoting healthy aging and longevity: An epidemiological perspective. Journal of internal medicine, 295(4), 508–531.