Researchers have investigated the reporting quality of preclinical studies’ outcomes in anti-aging research. They analyzed how study quality changed over time, shortcomings in research, and the improvements that can be made in the future in order to yield as many valuable insights as possible [1].

The need for quality

Aging research has grown substantially; however, conducting human trials in the aging field is time-consuming and requires substantial resources. Therefore, initial testing is done in preclinical models, such as mice, worms, fruit flies, and other model animals, as many genes, molecular processes, and aging mechanisms are conserved between those animals and humans [2]. To increase the likelihood of translating results from animal models to humans, high-quality studies are essential.

To assess the quality of preclinical studies in the anti-aging field, the researchers analyzed 667 studies published in peer-reviewed journals between 1948 and 2024, which included 720 experiments, from the DrugAge database. This is “a curated database of preclinical experiments investigating the effects of interventions on aging and lifespan in non-human animals.” The analyzed studies varied in the animal species they used, with a small fraction including more than one model organism. The researchers aimed to assess the quality of reporting, methodological rigor, the distribution of observed effect sizes, and the presence of biases in those studies.

Assessing quality

The researchers assessed the studies using the CAMARADES (Collaborative Approach to Meta-Analysis and Review of Animal Data from Experimental Studies) score. This score, which usually involves scoring studies accordingly to a 10-item checklist, allows for assessing methodological quality and risk of bias.

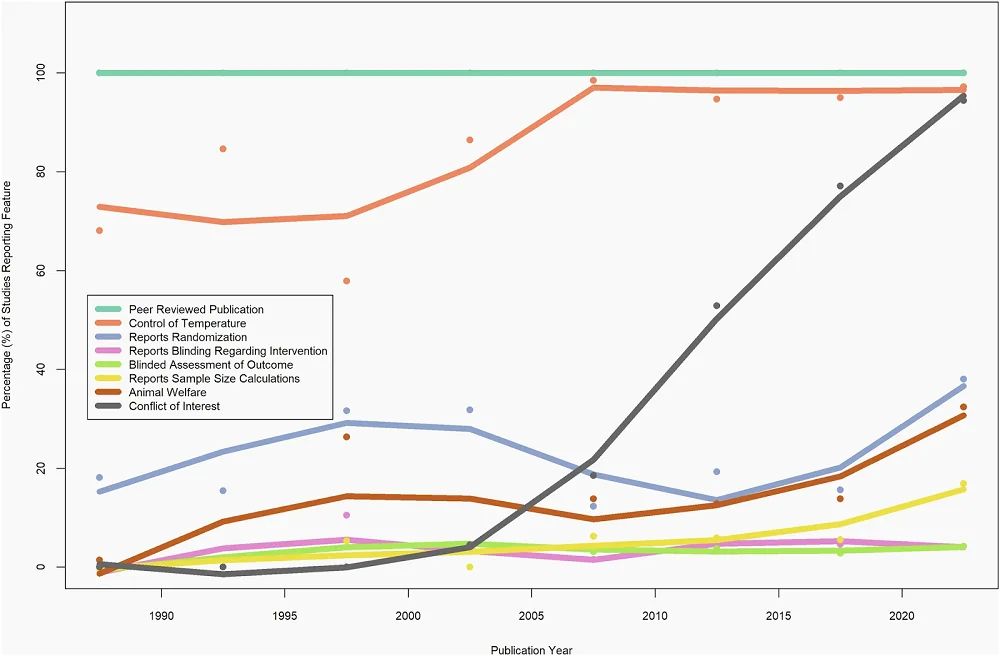

The median CAMARADES score across the analyzed studies was 3, but the researchers observed differences depending on the species used. Only two assessed parameters were consistent across all studies. First, all studies went through peer review. Second, blinding was generally absent. Specifically, blinding to intervention was discussed in only 4% of studies and blinded assessment of outcomes in 3%.

Among the assessed parameters, the researchers noted that almost one-fifth of studies mention randomization. Randomization, along with sample size calculation, was rarely reported when Caenorhabditis worms and Drosophila fruit flies were used, and overall, it was uncommon, with only 6% of all studies reporting it. However, studies using Caenorhabditis and Drosophila almost always gave information regarding the temperature at which animals were undergoing experiments. Temperature information was also common across all experiments, regardless of species used, with over 90% of analyzed studies reporting it. Those who didn’t report it mainly used mice. However, mouse studies did better with other parameters assessed by the researchers.

Other measured parameters included animal welfare, reported in 13.9% of studies, and conflict of interest statements, reported in more than half of the studies.

Since the studies used in the analysis spanned eight decades, the researchers analyzed how reporting changed over time. They noted that reporting of some parameters, especially conflicts of interest, compliance with animal welfare regulations, temperature control, and sample size calculations, increased over time, contributing to an increase in the CAMARADES score. However, there was no significant increase in reporting of randomization and blinding.

The critical parameters

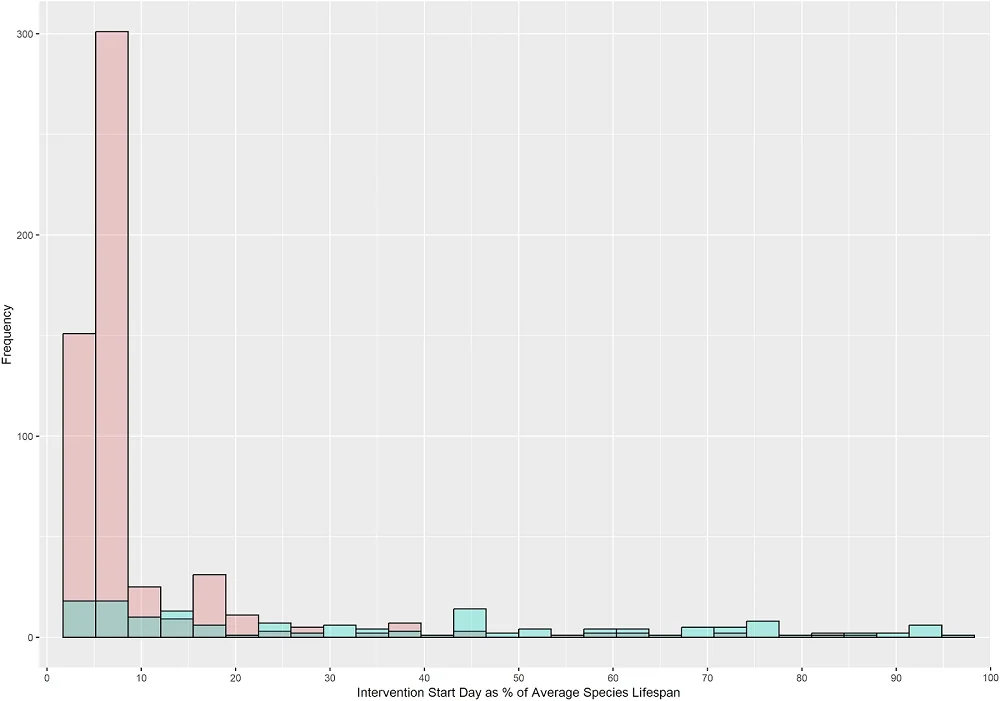

The critical parameter for anti-aging interventions is the timing of initiation, since there is a need for effective interventions that can extend lifespan when taken in mid-life or in the elderly, and the intervention’s effect might differ depending on the start time. However, among the analyzed experiments, the vast majority (over 80%) begin early in life, while only around 8% start at 50% of average lifespan or later, a gap that future studies should address. The researchers also note that, in the pre-clinical studies analyzed, mammal experiments tend to start later in lifespan than non-mammal experiments.

Another critical component in aging research is the animal’s sex. It is well known that there are sex-dependent differences in aging trajectories, and interventions should be assessed in both sexes, as they may respond differently to the same treatment. However, among the experiments analyzed by the authors that included animals that reproduce sexually, fewer than half used both sexes; 35.7% used only males, 12.9% used only females, and some didn’t report the sexes used at all.

Anti-aging compounds

The researchers noted that, among the studies in the DrugAge database, most compounds tested in non-mammalian models increased lifespan.

Additionally, the researchers compared the results between the mammalian and non-mammalian models. They noted that of 35 compounds tested in both mammalian and non-mammalian models, 21 significantly increased lifespan in non-mammalian models, but only one-third of those also significantly increased mammalian lifespan: curcumin, spermidine, epithalamin, D-glucosamine, estradiol, SKQ, and taurine. At the same time, two showed inconsistent results when compared to non-mammalian models, decreasing mammalian lifespan (quercetin and butylated hydroxytoluene). This suggests that in the case of those experiments, “non-mammal results do not seem to reliably predict mammal results, raising further concern for translation.”

The experiments in mammalian and non-mammalian models also differed in other parameters across compounds, including the median percentage increase in lifespan, which was smaller in mammalian models at 7.4% than in non-mammalian models at 17.5%.

Room for improvement

This study suggests that there is room for improvement in the way preclinical antiaging research is performed. The researchers noted that “important design features such as randomization, blinding of intervention, blinded assessment of outcome, compliance with animal welfare regulations, and sample size calculations were infrequently reported, despite evidence that the absence of such features can bias experimental results.” [3,4,5] Some of the most essential experiment design features, such as randomization and blinding, didn’t see substantial improvements over time. They conclude that “generally, most studies did not meet standard reporting guidelines for preclinical experiments.”

While this is not an excuse for failing to meet the standards necessary for high-quality research, those flaws are not limited to anti-aging research, as many studies addressing various diseases exhibit similar reporting and study design problems [6], suggesting a need for improvement.

Literature

[1] Parish, A., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Zhang, K., Barardo, D., R Swindell, W., & de Magalhães, J. P. (2025). Reporting quality, effect sizes, and biases for aging interventions: a methodological appraisal of the DrugAge database. npj aging, 11(1), 96.

[2] Kenyon C. (2001). A conserved regulatory system for aging. Cell, 105(2), 165–168.

[3] Schulz, K. F., Chalmers, I., Hayes, R. J., & Altman, D. G. (1995). Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA, 273(5), 408–412.

[4] Schulz, K. F., & Grimes, D. A. (2002). Blinding in randomised trials: hiding who got what. Lancet (London, England), 359(9307), 696–700.

[5] Kringe, L., Sena, E. S., Motschall, E., Bahor, Z., Wang, Q., Herrmann, A. M., Mülling, C., Meckel, S., & Boltze, J. (2020). Quality and validity of large animal experiments in stroke: A systematic review. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 40(11), 2152–2164.

[6] Kilkenny, C., Parsons, N., Kadyszewski, E., Festing, M. F., Cuthill, I. C., Fry, D., Hutton, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Survey of the quality of experimental design, statistical analysis and reporting of research using animals. PloS one, 4(11), e7824.