Genomic Instability

In this article, we explore DNA damage, its consequences, and how researchers are developing potential ways to repair it.

What is genomic instability?

Genomic instability is caused by DNA damage that isn’t repaired, as explained in the Hallmarks of Aging [1].

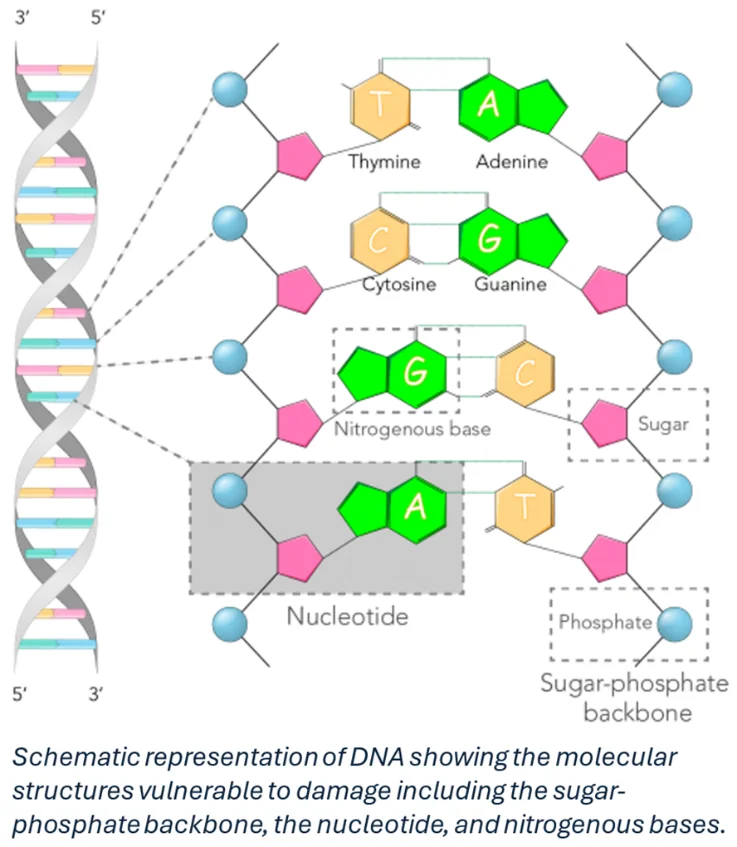

Our cells rely on a stable genome to transmit genetic material accurately. In the case of germline cells, genetic information passes from one generation to the next.

For our regular somatic cells, this means dividing to form new cells. This process includes the error-free replication of genetic material along with the repair of replication mistakes and damaged DNA.

Our cells use DNA as blueprints to make proteins and other materials needed for cell function and survival. However, during this process, a large amount of information contained in the DNA is ignored. This unused information is called junk DNA, the remnants of our evolutionary past.

DNA damage can affect genes and their transcription, resulting in dysfunctional cells that may jeopardize tissue integrity and function. This is especially important when the DNA damage affects stem cells, which reduces the supply of replacement cells for tissue renewal.

Damaged cells that cannot repair themselves often enter apoptosis, a self-destruct mechanism that marks it for removal by the immune system.

Genomic instability in aging

A few dysfunctional cell are not a huge problem, but with aging, an increasing number of cells succumb to DNA damage and begin to accumulate.

Eventually, the number of these damaged cells reaches a point where they can compromise organ and tissue function. The body usually removes these problem cells via apoptosis. Unfortunately, as we age, some cells evade apoptosis. These rogue cells take up space in the tissue and send harmful signals that damage the local tissue. They are senescent cells, and they are one reason we age.

Another possible outcome of damaged DNA is cells that mutate but do not destroy themselves. Instead, they continue to replicate, becoming increasingly mutated with each division. Cancer results if a mutation damages the systems that regulate cell division or disables tumor suppression. The unchecked and rampant growth of cancer is probably the most well-known consequence of DNA damage.

What is the cause of genomic instability?

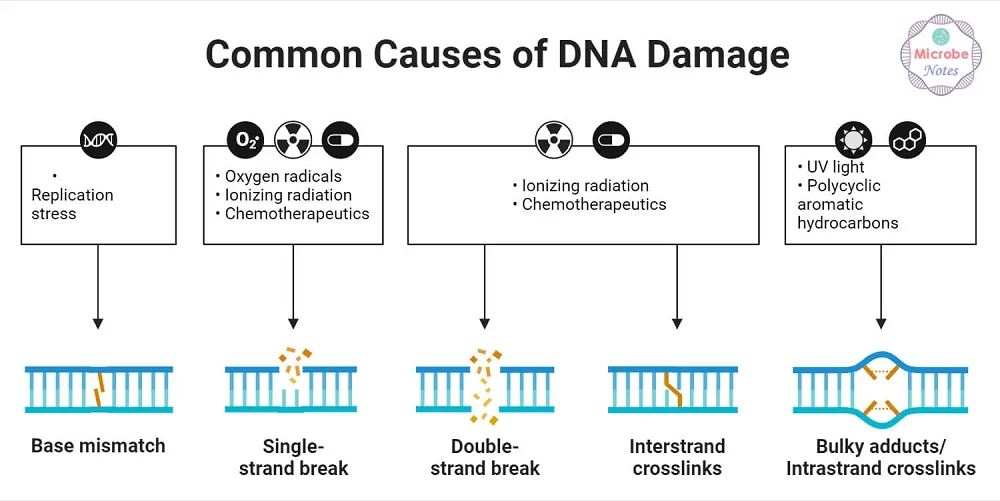

There are many ways for DNA to become damaged. UV rays, X-ray radiation, chemicals, and tobacco can all damage the genome. Even chemotherapy agents designed to kill cancer can also potentially damage DNA. Such toxic agents can also create senescent cells, leading to later relapse [2].

Finally, even without all the external threats to DNA, the body still damages itself. Oxidative stress produced by normal metabolism can damage nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Double-strand breaks are often the result of this metabolic damage and can be lethal to the cell.

Common causes of DNA damage [3]

How does DNA damage cause cancer?

Damaged DNA can lead to mutations, which cause the cell to become cancerous and multiply uncontrollably. A possible approach may be to develop therapies that boost DNA repair, thus reducing risk factors for the disease.

Another possibility is developing therapies that repair the genomes of cancer cells to make them normal cells again. Some initial demonstrations of this in cell studies have been made. A therapy that could restore genome stability may prove an effective cancer treatment, especially in relapse.

Cancer is the most well-known disease associated with DNA damage, but others are likely to be linked to genomic damage.

How does genomic instability cause progeria?

Progeric diseases are further examples. Progerias are congenital disorders that result in rapid aging-like symptoms and a dramatically shortened lifespan. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is probably the most well-known of these.

It is caused by a defect in Lamin A, an important part of the nuclear lamina, a protein structure in the nucleus. The lamina helps with DNA and RNA synthesis, and lamins support important proteins in the DNA repair process.

Sadly, HGPS sufferers typically only live until their early 20s due to their condition. They often develop atherosclerosis, stiff joints, hair loss, wrinkles, and other characteristics that are similar to accelerated aging.

How does the body deal with DNA damage, and can science improve on it?

Maintaining the integrity of genetic code is paramount for survival. Cells are equipped with sophisticated defense mechanisms to prevent and address myriad threats to DNA stability.

On the front lines, antioxidant systems vigilantly patrol the cell to neutralize harmful molecules that could damage DNA. These include enzymes and other molecules that scavenge reactive oxygen species, preventing them from wreaking havoc.

Meanwhile, when damage does occur, the cell’s DNA damage response system springs into action. This response balances repairing cell damage against the need to eliminate severely damaged cells.

These systems work together to protect DNA from errors that could cause disease. Therefore, scientists are taking cues from these existing systems to bolster the body’s antioxidant defense and DNA repair systems.

Antioxidant defense systems

Scientific efforts to improve antioxidant defense systems and DNA repair have been underway for several decades. Antioxidants gained popularity in the 1950s-60s when Dr. Denham Harman created the “free radical theory of aging” [4]. This theory proposed that aging results from accumulated free radical damage over time.

Free radicals, including reactive oxygen species, are unstable molecules that can damage DNA. Antioxidants can stop these molecules’ effects, possibly slowing aging and lowering the chance of chronic diseases.

Harman’s theory sparked increased interest in how oxidative stress affects aging and disease. This prompted more research on antioxidants to combat this damage.

By the 1970s-80s, the idea that antioxidants might extend life and prevent diseases had gained traction with the public. There was a surge in the sale of antioxidant supplements, including vitamins E and C, beta-carotene, and selenium.

Antioxidants became more popular in the 1990s-2000s due to studies and public interest in wellness and anti-aging products. However, the simplistic idea that antioxidants are always good and oxidants are always bad would be challenged.

Further studies revealed that antioxidant supplements could have varying or negative effects. These effects were more pronounced when the supplements were taken in high doses or outside their natural food context [5-7].

This led to a more nuanced understanding of how and when antioxidants can be beneficial. The focus shifted towards consuming antioxidants through a balanced diet rather than supplements.

Scientists are still studying how to boost the body’s natural antioxidants, despite mixed results from studies on antioxidant supplements. The goal to create better antioxidant defenses is still ongoing.

Unfortunately, dietary antioxidant supplements can sometimes interfere with critical cellular processes. They also may not target the specific types of oxidative damage that contribute most significantly to aging.

Developing more focused antioxidants

Scientists are developing targeted antioxidants to address the most damaging types of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within cells. If successful, this could prevent the potential off-target effects seen from using antioxidant supplementation.

This could potentially be more effective than general antioxidants by focusing on particular cellular compartments. This could be useful for mitochondrial dysfunction, in which reactive oxygen species cause damage and is another reason that people age.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is located very close to the electron transport chain within the mitochondria. The electron transport chain produces lots of reactive oxygen species, primarily due to the leakage of electrons. These reactive oxygen species can potentially damage nearby molecules, including the mtDNA.

Mitochondria–targeted antioxidants like MitoQ [8] and SkQ1 [9, 10] target the mitochondria and may potentially reduce oxidative stress. These compounds act like coenzyme Q10 and plastoquinone, which neutralize ROS in animals and plants, respectively.

A 2018 meta-analysis found that taking MitoQ supplements may help reduce oxidative stress in mitochondria with aging. However, the effects of MitoQ on other markers of oxidative stress and aging were unclear. Larger human studies are needed to fully understand the benefits of MitoQ in reducing oxidative stress and slowing aging.

Boosting antioxidant defenses

Researchers are also looking at boosting the body’s antioxidant systems to prevent genomic instability instead of just adding external antioxidants.

This approach aims to support the natural regulatory mechanisms that cells use to maintain oxidative balance. For example, one approach aims to increase activity in the Nrf2 pathway. This pathway can boost the body’s antioxidant defense mechanisms to improve genomic stability [11].

Another approach to bolstering endogenous antioxidants is introducing genes that encode powerful antioxidant enzymes directly into cells. This could potentially offer a more sustained and effective defense against oxidative damage.

For example, Tang used a modified virus containing the manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2) gene. This was delivered into eye cells in order to prevent retinal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. The treatment significantly reduced oxidative stress and protected the eyes from increased oxidative DNA damage [12].

Finally, indirect antioxidant approaches aim to reduce the production of ROS. This category includes caloric restriction mimetics and uncoupling proteins (UCPs).

Caloric restriction mimetics, such as resveratrol and rapamycin, directly improve mitochondrial function, modulate energy metabolism, induce autophagy, and enhance antioxidant defense.

UCPs act like a safety valve. They prevent excessive buildup of electrons in the electron transport chain, the energy-producing machinery of the mitochondrion [13, 14]. This protects the cell from oxidative damage and helps regulate energy efficiency within the mitochondria.

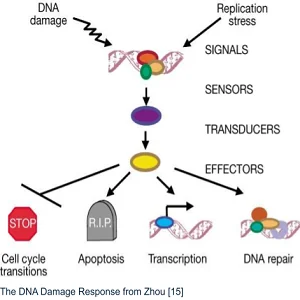

The DNA Damage Response

The DNA Damage Response (DDR) is a multilevel signaling pathway. It contains sensors that detect DNA damage, transducing proteins that pass the message of DNA damage along, and effectors. These proteins initiate the proper response based on what kind of molecular damage has occurred to the DNA.

That response can include cell cycle transitions, including temporary and permanent arrest (senescence). It can also trigger transcription, DNA repair, or even apoptosis if the damage is too severe [15]. The system’s complexity allows fine control, but it’s vulnerable to damage to the DNA code that generates proteins for the DDR system.

That response can include cell cycle transitions, including temporary and permanent arrest (senescence). It can also trigger transcription, DNA repair, or even apoptosis if the damage is too severe [15]. The system’s complexity allows fine control, but it’s vulnerable to damage to the DNA code that generates proteins for the DDR system.

Therefore, the integrity of this system is central to the maintenance of genomic stability. Understanding it is central to research efforts to improve its fidelity even further.

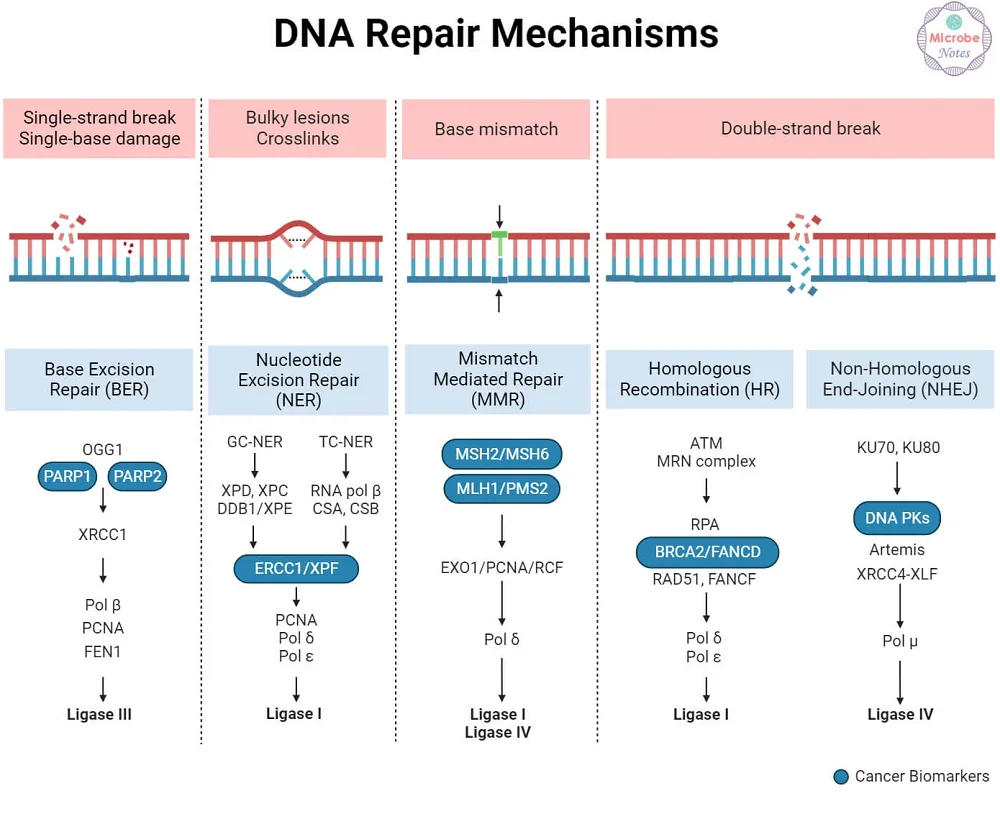

To solve this problem, scientists have focused on five basic DNA repair mechanisms. There are: nitrogenous base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, mismatch-mediated repair, homologous recombination, and non-homologous end-joining [3].

DNA damage that distorts the shape of DNA, such as adducts, is repaired by nucleotide excision repair.

DNA damage that distorts the shape of DNA, such as adducts, is repaired by nucleotide excision repair.

DNA glycosylase removes damaged bases in base excision repair. The phosphodiester bond is cleaved by endonucleases, and the correct base is added by DNA polymerase.

DNA ligase then seals the phosphodiester backbone. DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are the most cytotoxic and mutagenic DNA lesions. DSBs are repaired by homologous repair (HR) or nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) repair.

NHEJ is more common but is error-prone [3]. HR displays more fidelity, employing a homologous sequence as a template for repair.

Mismatch-mediated repair (MMR) replaces mispaired bases that are damaged and, if not replaced, would result in heritable mutations. MMR is usually needed for errors in DNA replication and recombination.

Aging itself is not considered a disease, so most research is focused on diseases linked to abnormal DNA repair. DNA repair system defects are caused by mutations in repair protein code. Scientists are trying to fix this by replacing damaged DNA codes with corrected ones.

The most popular techniques for doing this are traditional gene transfer and editing technologies. These enable the deletion and insertion of the DNA that codes for the various DNA repair pathways [16].

Genes are transferred into the body using vectors like viruses and liposomes. These vectors can naturally enter specific cells and deliver genetic material efficiently. The genetic material can be delivered permanently or temporarily.

Traditional gene transfer methods can struggle to target the right spot in DNA. This can then lead to an unwanted knockout of a functional gene [16].

Gene editing tools

Gene editing tools include CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, ZFNs, and base and prime editors. CRISPR-Cas9 is the most famous and widely used gene editing technique. The CRISPR-Cas9 system was created by re-engineering a natural defense mechanism in bacteria. This system normally protects these organisms from invading viruses and plasmids.

It allows for very precise editing of DNA at specific locations [16]. Base editors are a more recent innovation derived from CRISPR technology. Base editors allow users to change one base in DNA without causing or repairing a double-strand break in the DNA [17].

Prime editing is another recent development derived from CRISPR technology. It is superior to CRISPR-Cas9 editing because it doesn’t require the creation of potentially hazardous double-strand breaks. Also it is more precise, reducing any possibility of off-target effects [18].

More than two dozen enzymes are involved in the five DNA repair processes. It is theoretically possible to create permanent or temporary changes in these enzymes to repair mutations in them. Beyond that, they could potentially be improved to emulate the mechanisms found in longer-lived species.

Gorbunova et al. performed a detailed analysis of the DNA repair systems of mice, naked mole rats, and humans. This study offered invaluable information that could be used to improve the DNA repair efficiency of people. It identified 12 DNA genes involved in repair that were upregulated in the naked mole rat. The greater expression of these genes in these animals suggests that they have more effective DNA repair. This more robust system likely contributes to their extreme longevity and resistance to cancer [19].

Fanconi anemia

This condition is caused by mutations in genes that help fix DNA, especially the ones that repair DNA crosslinks. CRISPR has been used to correct mutations in FANCA and FANCC genes in patient-derived cells, restoring normal function [20].

Xeroderma pigmentosum

Patients with this condition are very vulnerable to UV-induced DNA damage. This is due to gene mutations in the nucleotide excision repair pathway. CRISPR has been used to correct mutations in genes like XPC, which is crucial for initiating the repair of UV-induced DNA lesions [21, 22].

Cancer research

CRISPR has been used to study and potentially reverse gene mutations such as BRCA1 and BRCA2. These genes are involved in the homologous recombination pathway, a key mechanism for repairing double-strand DNA breaks. Correcting these mutations may restore normal DNA repair and reduce the likelihood of cancer [23-25].

These studies serve as proof of principle and a beacon of hope that aging DNA damage repair systems can be fixed. There is also the potential for them to be upgraded to significantly extend health and lifespan.

Conclusion

Despite the various repair systems that humans have evolved, the human body is constantly being assaulted by exposure to environmental stressors and its own metabolic processes. The body’s repair systems also decline in effectiveness over time, meaning that DNA damage and mutations are inevitable. Some evidence suggests that caloric restriction may help combat this, but no drugs or therapies can prevent or repair DNA damage.

The good news is that human trials for DNA repair are launching this year (2024) at Harvard, and other researchers are also working on potential solutions. One thing is almost certain: rejuvenation biotechnology must find ways to repair the genome to reduce cancer risk with age, thus opening up the possibility of longer lifespans.

For now, the best we can do is avoid risks such as excessive sun exposure, industrial chemicals, and smoking; of course. We should also avoid radioactive waste, as these mutations do not give us comic book superpowers!

Literature

[1] López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194.

[2] Demaria, M.; O’Leary, M.N.; Chang, J.; Shao, L.; Liu, S.; Alimirah, F.; Koenig, K.; Le, C.; Mitin, N.; Deal, A.M.; et al. Cellular Senescence Promotes Adverse Effects of Chemotherapy and Cancer Relapse. Cancer Discov 2017, 7, 165–176.

[3] DNA Damage and DNA Repair: Types and Mechanisms Available online: https://microbenotes.com/dna-damage-and-repair/ (accessed on 21 April 2024).

[4] Harman, D. Free Radical Theory of Aging. Mutation Research/DNAging 1992, 275, 257–266.

[5] Nimse, S.B.; Pal, D. Free Radicals, Natural Antioxidants, and Their Reaction Mechanisms. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 27986–28006.

[6] Steinhubl, S.R. Why Have Antioxidants Failed in Clinical Trials? American Journal of Cardiology 2008, 101.

[7] Attia, M.; Essa, E.A.; Zaki, R.M.; Elkordy, A.A. An Overview of the Antioxidant Effects of Ascorbic Acid and Alpha Lipoic Acid (In Liposomal Forms) as Adjuvant in Cancer Treatment. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1–15, doi:10.3390/antiox9050359.

[8] Pham, T.; MacRae, C.L.; Broome, S.C.; D’souza, R.F.; Narang, R.; Wang, H.W.; Mori, T.A.; Hickey, A.J.R.; Mitchell, C.J.; Merry, T.L. MitoQ and CoQ10 Supplementation Mildly Suppresses Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Hydrogen Peroxide Levels without Impacting Mitochondrial Function in Middle-Aged Men. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2020 120:7 2020, 120, 1657–1669.

[9] Huang, B.; Zhang, N.; Qiu, X.; Zeng, R.; Wang, S.; Hua, M.; Li, Q.; Nan, K.; Lin, S. Mitochondria-Targeted SkQ1 Nanoparticles for Dry Eye Disease: Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Preventing Mitochondrial DNA Oxidation. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 365, 1–15.

[10] Anisimov, V.N.; Egorov, M. V.; Krasilshchikova, M.S.; Lyamzaev, K.G.; Manskikh, V.N.; Moshkin, M.P.; Novikov, E.A.; Popovich, I.G.; Rogovin, K.A.; Shabalina, I.G.; et al. Effects of the Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant SkQ1 on Lifespan of Rodents. Aging (Albany NY) 2011, 3, 1110.

[11] Nguyen, T.; Nioi, P.; Pickett, C.B. The Nrf2-Antioxidant Response Element Signaling Pathway and Its Activation by Oxidative Stress. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284, 13291–13295,.

[12] Liu, Y.; Tang, L.; Chen, B. Effects of Antioxidant Gene Therapy on Retinal Neurons and Oxidative Stress in a Model of Retinal Ischemia/Reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med 2012, 52, 909–915.

[13] Rose, G.; Crocco, P.; De Rango, F.; Montesanto, A.; Passarino, G. Further Support to the Uncoupling-to-Survive Theory: The Genetic Variation of Human UCP Genes Is Associated with Longevity.

[14] Carrageta, D.F.; Freire-Brito, L.; Guerra-Carvalho, B.; Bernardino, R.L.; Monteiro, B.S.; Barros, A.; Oliveira, P.F.; Monteiro, M.P.; Alves, M.G. Mitochondrial Uncoupling Proteins Regulate the Metabolic Function of Human Sertoli Cells. Reproduction 2024, 167.

[15] Zhou, B.B.S.; Elledge, S.J. The DNA Damage Response: Putting Checkpoints in Perspective. Nature 2000, 408, 433–439.

[16] Liu, G.; Lin, Q.; Jin, S.; Gao, C. The CRISPR-Cas Toolbox and Gene Editing Technologies. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 333–347.

[17] Rees, H.A.; Liu, D.R. Base Editing: Precision Chemistry on the Genome and Transcriptome of Living Cells. Nature Reviews Genetics 2018 19:12 2018, 19, 770–788.

[18] Anzalone, A. V.; Koblan, L.W.; Liu, D.R. Genome Editing with CRISPR–Cas Nucleases, Base Editors, Transposases and Prime Editors. Nature Biotechnology 2020 38:7 2020, 38, 824–844.

[19] MacRae, S.L.; Croken, M.M.K.; Calder, R.B.; Aliper, A.; Milholland, B.; White, R.R.; Zhavoronkov, A.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V.; et al. DNA Repair in Species with Extreme Lifespan Differences. Aging 2015, 7, 1171–1184.

[20] Osborn, M.J.; Gabriel, R.; Webber, B.R.; Defeo, A.P.; McElroy, A.N.; Jarjour, J.; Starker, C.G.; Wagner, J.E.; Joung, J.K.; Voytas, D.F.; et al. Fanconi Anemia Gene Editing by the CRISPR/Cas9 System. https://home.liebertpub.com/hum 2014, 26, 114–126.

[21] Goncalves-Maia, M.; Magnaldo, T. Genetic Therapy of Xeroderma Pigmentosum: Analysis of Strategies and Translation. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 2017, 5, 5–17.

[22] Nasrallah, A.; Rezvani, H.-R.; Kobaisi, F.; Hammoud, A.; Rambert, J.; Smits, J.P.H.; Sulpice, E.; Rachidi, W. Generation and Characterization of CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated XPC Gene Knockout in Human Skin Cells. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.01.25.577199, doi:10.1101/2024.01.25.577199.

[23] Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Khorramian-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Shafieizadeh, M.; Mahmoudi, E.; Eskandari, F.; Rashidi, M.; Arshi, A.; Mokhtari-Farsani, A. Comprehensive Review of CRISPR-Based Gene Editing: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Applications in Cancer Therapy. Molecular Cancer 2024 23:1 2024, 23, 1–45, doi:10.1186/S12943-023-01925-5.

[24] Walton, J.; Blagih, J.; Ennis, D.; Leung, E.; Dowson, S.; Farquharson, M.; Tookman, L.A.; Orange, C.; Athineos, D.; Mason, S.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Trp53 and Brca2 Knockout to Generate Improved Murine Models of Ovarian High-Grade Serous Carcinoma. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 6118–6129, doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1272/652458/AM/CRISPR-CAS9-MEDIATED-TRP53-AND-BRCA2-KNOCKOUT-TO.

[25] Khalil, M.I. CRISPR/Cas9 Design to Knockout and Knockin the Breast Cancer Gene-BRCA1 in Arabidopsis Thaliana. J Phys Conf Ser 2020, 1660, 012009, doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1660/1/012009.