Recently published research in Cell Reports provides a detailed account of dietary spermidine improving cognition and mitochondrial function in flies and mice, with some prospective human data to top it off.

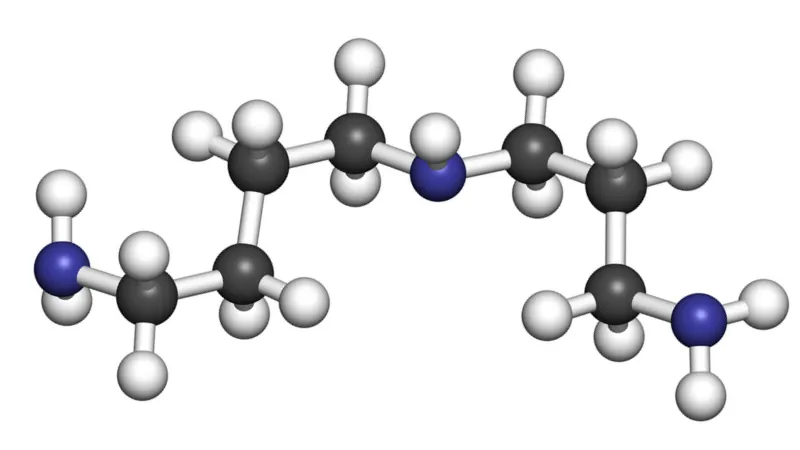

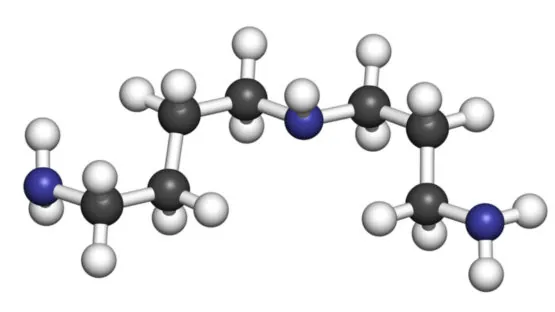

Spermidine and longevity

Spermidine is known to decline with aging, and treatment with spermidine extends lifespan across various species. While it has a myriad of potentially beneficial effects, spermidine has been most clearly demonstrated to impact autophagy and mitophagy, promoting the removal and replacement of damaged mitochondria in both mice and flies. It is one of the most highly studied longevity compounds, including in the brain, where intra-abdominal and intra-cerebral spermidine injections have been shown to enhance cognition both in aged mice and in transgenic models of neurodegeneration.

Can dietary spermidine achieve similar results?

A large collaboration based at the University of Graz in Austria has studied spermidine when supplied continuously via drinking water rather than intermittently with injections [1]. Spermidine was found to cross the blood-brain barrier in aged male and female mice. In male mice, it also moderately improved a variety of behavioral tests of cognition at an old age of 24 months.

Interestingly, female mice and male mice receiving the higher dose investigated by the researchers did not see as much positive improvements as the male mice treated with the lower dose. This suggests that more dose-response studies, particularly regarding sex differences, are needed on spermidine and cognitive function.

When the researchers delved into the mechanisms of action of their treatment, they did not find an activation of known NMDA receptor targets, which occurred in similar studies that delivered spermidine via injection. However, they did find improved respiratory capacity (a measure of mitochondrial function) in the hippocampi of aged mice and in the heads of fruit flies.

To show that this effect was mediated by autophagy, the researchers knocked out Atg7, a key gene essential to autophagy in the fruit flies. In these flies, spermidine no longer had the previously seen benefits on mitochondrial function. Similar results were seen by knocking out Pink1 or Park, genes involved in mitophagy, suggesting that these specific pathways are involved.

Spermidine in our regular diets

Finally, the researchers analyzed an existing dataset within the Bruneck study that followed the diet and cognitive function of older adults over time. Dietary spermidine intake was estimated based on self-reported food frequency questionnaires and was stable over time within individuals. After adjusting for age, sex, and caloric ratio, spermidine intake was correlated with various measures of cognitive function and reduced the odds of developing cognitive impairment.

These findings held regardless of sex, social status, and level of education, whether various adjustments were made (i.e. excluding subjects with depression) or whether the data was analyzed as continuous or if subjects were grouped into low/medium/high spermidine intake cohorts. Since spermidine also correlates with other nutrients, the authors also controlled for their results using the Alternate Healthy Eating Index. The benefits of spermidine remained significant, suggesting that the correlation goes beyond a healthy eating pattern.

The combination of epidemiological and experimental data raises the intriguing possibility that dietary SPD may be protective against cognitive decline in humans. Elevated intake of SPD has recently been shown to be safe in healthy, elderly humans (Schwarz et al., 2018). In a phase II trial including subjects with self-reported cognitive decline, SPD led to detectable improvements in cognition already after a 3-month treatment period (Wirth et al., 2018). We herein propose that dietary SPD acts in a neuroprotective manner during normal aging. The beneficial effects of SPD appear to depend on autophagy- and likely mitophagy-related processes that culminate in improved mitochondrial capacity, at least in model organisms. Accordingly, the straightforward and inexpensive availability of nutritional SPD in the human diet may provide a potent strategy to prevent the course of age-related or disease-driven cognitive decline in the general population.

Conclusion

This study provides novel data on the effects of spermidine on the aging brain when delivered through the diet. It also sheds light on its mechanisms of action for improving cognition, highlighting the role of mitophagy. Not many studies utilize flies, mice, and humans concurrently. This study’s application to all three species makes for more robust and convincing results. However, it should be noted that the cliché “correlation not causation” fundamentally applies to the researchers’ analysis of the human dataset.

There are many other factors that are impossible to control for and may also be at play. Nonetheless, this study adds to our understanding of spermidine as a therapeutic agent and further justifies its investigation in clinical trials for longevity and cognitive decline, some of which are currently ongoing [2].

Literature

[1] Schroeder, S., Hofer, S.J., Zimmermann, A., Pechlaner, R., Dammbrueck, C., … & Madeo, F. (2021). Dietary spermidine improves cognitive function. Cell Reports, 35(2), 108985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108985

[2] Wirth, M., Benson, G., Schwarz, C., Köbe, T., Grittner, U., … & Flöel, A. (2018). The effect of spermidine on memory performance in older adults at risk for dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Cortex, 109, 181-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2018.09.014